Report Published May 1, 2010 · Updated May 1, 2010 · 16 minute read

Preparing for a Successful Retirement

Cristy Gallagher, Jim Kessler, Tess Stovall, & Mark Sagat

In the past, retirement was managed for people by their employers; now people are mostly on their own to figure out their own plan. That means that the decisions people make by age 35 about whether, how much, and where to invest their retirement accounts and the decisions they make at age 50 about their long-term care needs will have a substantial impact on the life they live when they are 80.

THE PROBLEM

Preparing for retirement has become more complex and

more confusing.

Today, there is greater uncertainty in retirement planning.

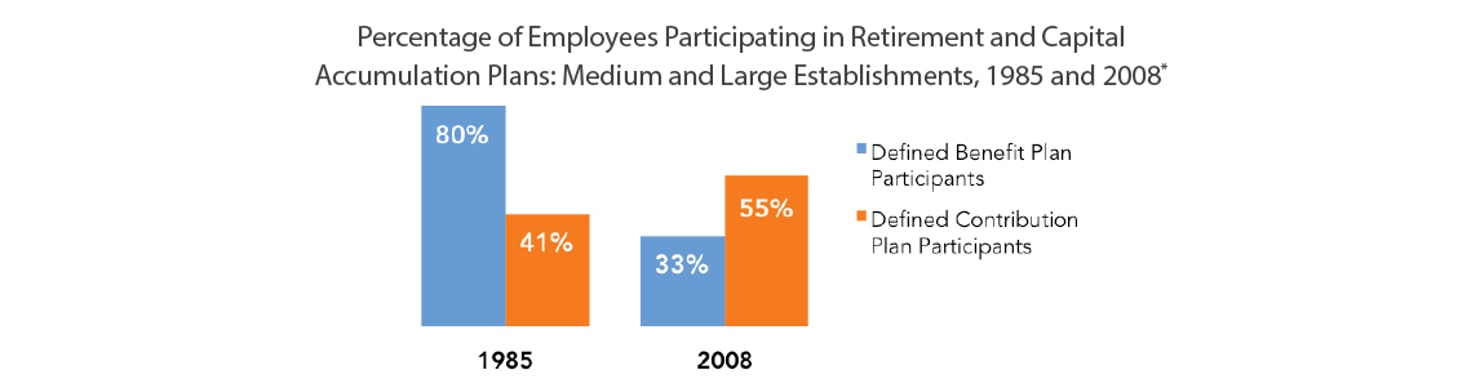

In the private sector, the defined benefit pension plan—where a worker would receive a monthly retirement check based on the years they worked and the salary they earned—is a relic of the past. It has been replaced with defined contribution plans where workers decide to invest in retirement accounts on their own, often with an employer contribution.

Source: Employee Benefit Research Institute, “EBRI Databook on Employee Benefits: Participation in Employee Benefit Programs,” July 2008, available at http://www.ebri.org/publications/books/index.cfm?fa=databook.

* Includes only those retirement plans that do not allow withdrawal of employer contributions until retirement age, death, disability, separation from service, age 59 ½ and hardship. Some retirement plan participants had both defined benefit and defined contribution plans.

Some believe the old system is better, others don’t. But the fact is that there is almost no chance that the private sector will return to a defined benefit system. This means that workers have far greater responsibility in planning their own retirements and the mistakes they make, or a run of bad luck, can make the difference between a comfortable retirement and a lean one. What used to be simple is now complicated. What used to be certain; now contains risk.

Young people are not saving for their retirements.

One mistake is prevalent among those under the age of 35. Many workers simply do not contribute to any retirement vehicle at a young age1—wasting many years that they could be saving for a comfortable and successful retirement. For example, less than half of all adults under the age of the 35 have a 401(k) or IRA plan at all.2

Even if they do contribute, roughly half opt to cash out when switching employers3—even though such a decision comes with a federal tax penalty. And because the system is so complicated, most people just flat out don’t understand financial planning and therefore make poor investment choices.

All of this is critical because the value of early money put into a retirement account is far greater than later money.

As individuals are living longer, retirement is lasting longer.

Life expectancy is longer today than it has ever been, and the result will be that many people won’t have enough savings to maintain their lifestyle during retirement. A person retiring today at the age of 65 can expect to live nearly 19 years. 50 years ago that person could expect to live only 14 years.4 Three out of five retirees can expect to outlive their retirement savings if they maintain their pre-retirement standard of living.5 And to top it off, with the longer life expectancy, is the increased need for long term care, which most Americans are not prepared for. In this paper, we lay out solutions to help individuals better plan for the retirement they have worked for and deserve.

THE SOLUTIONS

Make it easier to plan for retirement

For governors, federal law, unfortunately, limits what states can do to improve many present retirement planning practices. The federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) preempts most state laws relating to retirement plans. Similarly, the federal tax code dictates what type of retirement contributions can be considered a tax-benefit, thereby inhibiting states’ abilities to provide tax incentives that encourage people to contribute to certain retirement accounts.

Despite these limitations, we’ve identified five new ideas that states can deploy to make it easier to save for retirement.

1. Match workers’ contributions to retirement accounts for residents under 30.

Only 12.5% of workers 25 and under owned an IRA or 401(k) retirement plan in 2005, and just 43.8% of workers under 35 owned an IRA or 401(k) plan.6 Because early money is so important when contributing to a retirement account, it is essential to encourage younger workers to begin saving as soon as possible. To encourage these young workers to start saving earlier and save more, states could provide workers between the ages of 22 and 30 an annual match of up to $300 for their contributions to a traditional or Roth IRA, up to a lifetime total of $1200. This match could be provided as a non-refundable tax credit and be deposited directly in the IRA account provided by such workers on their tax returns.

For example, in a state like Colorado, if one-third of the eligible population received the full match, this program would provide approximately $48 million a year to young people’s retirement accounts.7 If the investment grew by a modest 4% in real terms, by retirement age this would be worth roughly $200 million in today’s dollars.

2. Allow the direct deposit of state income tax refunds into retirement accounts.

Today, 35 states allow individuals to have their state income tax refunds directly deposited into their savings or checking accounts, and as many as one-third of filers took advantage of this option in 20048 In California, nearly 4 million tax filers chose this option in 2008.9 However, directly depositing a state income tax refund in a checking or savings account provides money for today’s expenses, not tomorrow’s savings. To ensure that people save adequately for their retirement, states should enact policies to ensure that individuals can directly deposit any tax refunds they receive into traditional retirement accounts.

Federal law, though, limits what states can do in this area. Under the federal tax code, contributions to 401(k) style plans can only be made from salaries or wages by the employer on behalf of the employee. In addition, state involvement in 401(k) plans could potentially subject such states making such contributions to ERISA fiduciary liability. Until there is a change in the law, this plan would be limited to holders of Roth IRAs or other after-tax investment vehicles.

Best Practices

- Hawaii is one example of a state that already allows individuals to split their tax refunds into multiple accounts.10 Hawaii began this process in 2008, and by doing so, Hawaii is working to ensure that its citizens are saving for tomorrow as well as today.

3. Mandate financial education for high school students and college students.

Young people today are entering a world with many more opportunities for building wealth, but also more complexity and risk. In the past, it was enough to have only a checking and savings account, along with a job that offered a traditional pension. Loan instruments for buying a house were fairly simple and limited. But all of that has changed. As we’ve learned, home loans can be exceptionally complex. Whether it’s managing investments in a retirement account, understanding the fine print on a mortgage application, avoiding credit fees or knowing how to monitor a credit report, managing one’s finances is more complicated than it used to be.

To get ahead in a world that takes market savvy, not just book smarts, today’s young people need to acquire skills to understand investing. Financial education should become a mainstay of the modern school curriculum, so young people will be better able to make the financial choices that will have a long term effect on their financial well-being.

A growing pile of research shows that financial education can help people make better financial decisions. Three in five students who took a financial literacy class reported an increased knowledge of the cost of credit, auto insurance and investments.11 After the financial literacy class ended, 59% of students reported that they had changed their spending patterns and 60% of students reported that they had changed their savings patterns.12 Studies have found direct links between the level of financial knowledge a person has and the decisions they make—the amount they save, whether they pay bills on time, etc.13 And students in states with mandatory financial education have higher savings rates five years down the line than students in states without such a requirement.14 Forty-one percent of students who’ve had financial education also report feeling much more confident about making the right choices.15

Some experts believe that financial education is best taught at a college level to students who are experiencing, some for the first time, financial independence. Therefore, in addition to requiring financial literacy be taught in high school, a state could suggest that both four-year and two-year colleges and universities incorporate a financial education course into the core curriculum.

Best Practices

- Missouri, Tennessee, and Utah require that a one-semester course on personal finance be taken before high school graduation.16 Nevada recently mandated that financial literacy be taught to high school students in a package of education reforms passed this year.17

- Georgia’s Governor launched a website called “Consumer Ed” to help walk customers through major financial decisions.18 Kentucky also launched a money management site, which provides financial information to citizens of the state, including retirement information.19

- In legislation to protect citizens from bad predatory lending, Delaware chose to apply a fee charged to new payday lenders setting up shop in the state to help fund literacy education. The lead House sponsor of the bill claimed that, “Using the revenue generated by the fee to fund financial literacy and loan programs is a great way to help the very people who use cash advances, educating them so that they can better manage their finances.”20

- At California State University, Northridge, one of the system’s largest campuses, students who receive student loans must enroll in a financial literacy course. Of the nearly 36,000 students on campus, almost half of them receive loans.21

- Barnard College in New York City also offers a financial literacy course for first-year students during their orientation. The one week course focuses on the basics of financial literacy such as making a budget.22

- Texas Tech has started the “Red to Black” program to help members of the Texas Tech community including students, faculty, and staff, make responsible financial decisions. Students can make an appointment for a free confidential financial counseling session.23

4. Call for changes in federal law so states can more actively provide retirement benefits.

States’ abilities to help people prepare for retirement are constrained by federal law. ERISA preempts most state laws relating to retirement plans, and the tax benefits afforded to certain types of retirement plans are creatures of federal law. In the absence of these constraints, there are a number of policies that states could implement to help the middle class save for retirement. For example, if ERISA and the federal tax code were amended, states could provide a match to 401(k) contributions made by employees or eliminate vesting requirements that make employees wait months before they can participate in their company’s pension plan or 401(k). States could also establish 401(k) plans to ensure that the benefits of a tax-deferred 401(k) account are open to everyone, including those individuals who do not have access to a plan by employers. By calling for limited changes to ERISA and the federal tax code, states will be able to more effectively and more comprehensively assist their citizens in planning for their retirement.

5. Discourage cash-outs and streamline the consolidation of 401(k) accounts for workers changing jobs.

Cashing out a retirement plan early is almost always a bad idea, yet nearly half of all workers who switch jobs cash out their 401(k).24 The Government Accountability Office in a recent report found that few employers provide information on the negative impact that cash-outs have on retirement savings when employees separate from the company. The GAO recommends that employers provide employees leaving companies information on the long-term consequences of various scenarios with their retirement plans, including cashing-out.25 The State Treasurer could embark on an education campaign that would encourage people to consolidate their 401(k) plans from former employers into an IRA and discourage cash-outs when changing jobs. States could host informational sessions to help people learn how to consolidate their plans into a retirement vehicle or set up a website and/or 1-800 phone line in partnership with an investment firm to help educate people on their options.

Prepare for Long-Term Care Needs

Roughly three in four Americans will need long-term care during their lifetimes.26 However, many Americans both underestimate the cost of long-term care and are unprepared for the potentially heavy expense of care. We have identified five ideas that governors can use to make it easier for people to prepare for their long-term care needs.

1. Create a state registry of elder care workers.

When families try to find someone to come into their loved one’s home to help with activities around the house, they often face the daunting task of having to search the internet for someone reliable. States could create an online registry of home care aides so that individuals and families have an easier time finding a qualified worker to help care for their loved ones. The registry can include previous employment information, training information, and background check information.

Best Practices

- Recently, the Governor of New York signed into law a bill that creates a central registry of home health and personal care aides. The registry lists the names and contact information of the aides along with background information, employment history, and training information.27 Illinois, Oregon, and Washington also have variations of home care worker registries.

2. Educate Americans about the need for long-term care insurance.

Many Americans underestimate the cost of long-term care. They are unprepared for the potentially heavy expenses of long-term care, which are not adequately covered by either Medicare or traditional insurance. They also have misperceptions about Medicare’s coverage of long-term care and often mistakenly believe that their private insurance will cover them if they need care in a nursing home or skilled nursing facility.28 Given that the average annual cost of nursing home care in 2009 was $74,208 for a private room,29 the need for long-term care insurance is significant. Still, only 10% of Americans aged 65 and older have private long-term care insurance.30 Governors have an even greater interest in helping their citizens attain long-term care insurance since states are responsible for paying nursing home costs for seniors who do eventually qualify for Medicaid in their states—a huge and growing cost to state budgets.

States could expand public campaigns to increase awareness of the need for long-term care planning to minimize an individual’s out-of-pocket costs.

Best Practices

- The National Clearinghouse for Long-Term Care Information began a campaign in 2005 called Own Your Future in which governors of five states sent packets offering long-term care planning assistance to every household with individuals aged 50 to 70.31 The overall response rate was approximately 8%, which is significantly higher than the typical response rate to comparable private sector direct mail campaigns. Today, 21 states participate in the program.32 A national program that builds on this model or increases the number of states that participate could prove to be equally successful in educating more Americans about the need to plan for long-term care costs.

3. Provide a match to help pay for the cost of long-term care insurance premiums.

Though long-term care insurance (LTCI) isn’t right for everyone, it has tremendous potential to alleviate the burden of out-of-pocket costs for seniors and their families and can also lessen the burden of long-term care costs on federal and state spending. The premiums are relatively expensive. The average annual premium for a LTCI policy in 2007 was $2,207. Beneficiaries aged 50 to 59 paid $1,982 annually, on average, while those over age 70 paid $3,026.33 While long-term care insurance can be significantly less expensive when purchased at a younger age, most buyers are older. At the time of purchase, the average age is 61.34 Significantly, 58% of people who did not purchase long-term care insurance cited cost as the most important reason as to why they did not purchase it.35

To encourage individuals to purchase long-term care insurance and to help offset the costs associated with its purchase, states could provide a match of $250 beginning at age 50 and ending at age 60, up to a lifetime of $1000. In states with an income tax, this match would come in the form of a non-refundable tax credit while in other states the state government would provide a check to the individual. In both instances, the individual would have to provide proof of purchase from a qualified long-term care insurer. If the program were successful enough to double the amount of people who purchased long-term care insurance to 20%, in a state like Tennessee, this proposal would cost approximately $14,000,000.36 Some of this cost, though, would also be offset by savings to Medicare and Medicaid programs that no longer would have to pay for long-term care services for these elderly individuals.

4. Create a simplified disclosure for long-term care insurance.

Long-term care insurance can help many Americans to better plan for their long-term care needs and save them and their families from many out-of-pocket expenses. While many should be looking into long-term care insurance, the complexity, length and dense jargon can make shopping for a policy extremely difficult. Of those who considered buying long-term care insurance but did not, 40% said that the confusing nature of the policy was an important or very important reason in their decision not to purchase it.37

Governors should call on the National Association of Insurance Commissioners to develop a simplified disclosure form for the long-term care insurance policies sold in all fifty states. Until a disclosure form is implemented on the national level, a governor, in conjunction with the state insurance commissioner, can develop a disclosure form to be used on all long-term care policies sold in the state. The disclosure form can provide consumers with clarity regarding a particular policy’s coverage benefits and allow for easy comparison of multiple policies. At a minimum, the disclosure form could use plain English and include consistent definitions for services and benefits, consistent format, and consistent disclosure of key policy provisions.

5. Expand so-called “Cash & Counseling” programs.

This Medicaid waiver program, created in the 1990s, provides elderly beneficiaries with a monthly budget to pay for personal care and can be used to pay friends and family under certain guidelines. Originally, three states (New Jersey, Arkansas and Florida) participated in this program. Now, a total of fifteen states participate in the program.38 In the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, the federal government made it easier for states to introduce Cash & Counseling programs by not requiring states to have federally-approved waivers in order to offer flexible budget options to eligible participants and their families.39