Report Published March 15, 2024 · 14 minute read

Uncared for and on the Edge: The Economic Reality of Non-College Women

Curran McSwigan

Takeaways

Women without a degree are close to the economic edge. Our research shows:

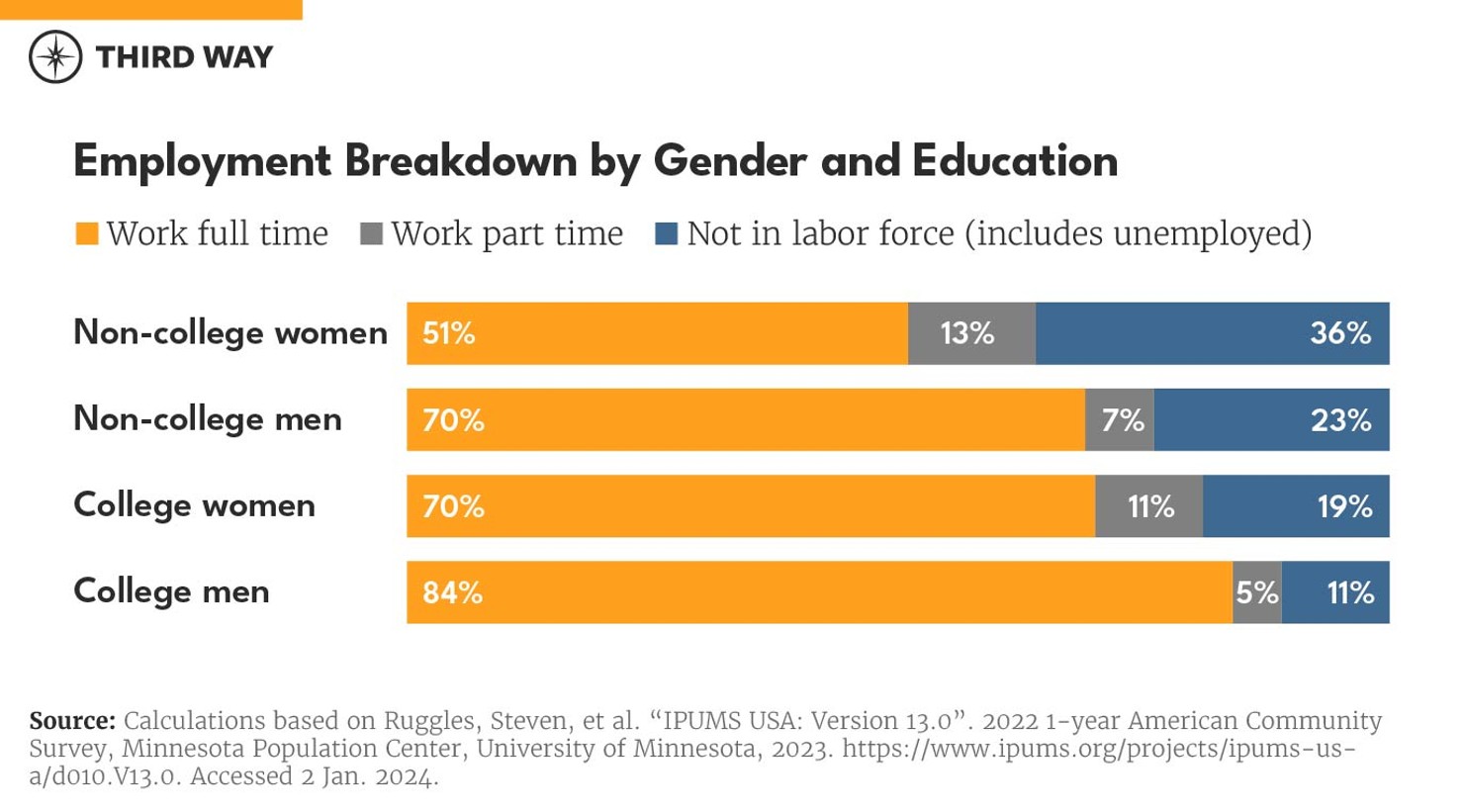

- Only half of working-age non-college women are employed full time.

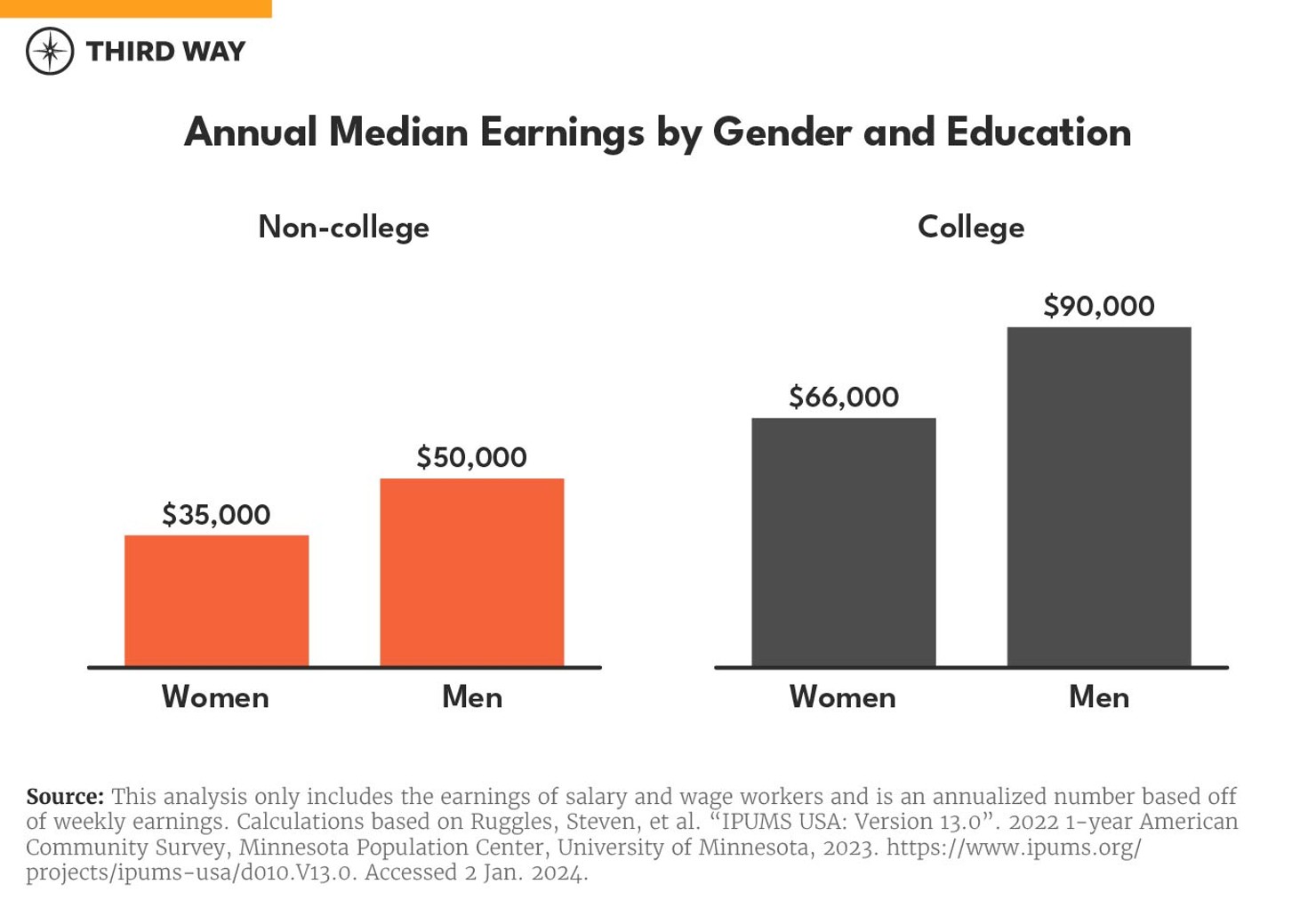

- Median earnings for non-college women are $35,000 a year, 30% lower than non-college men.

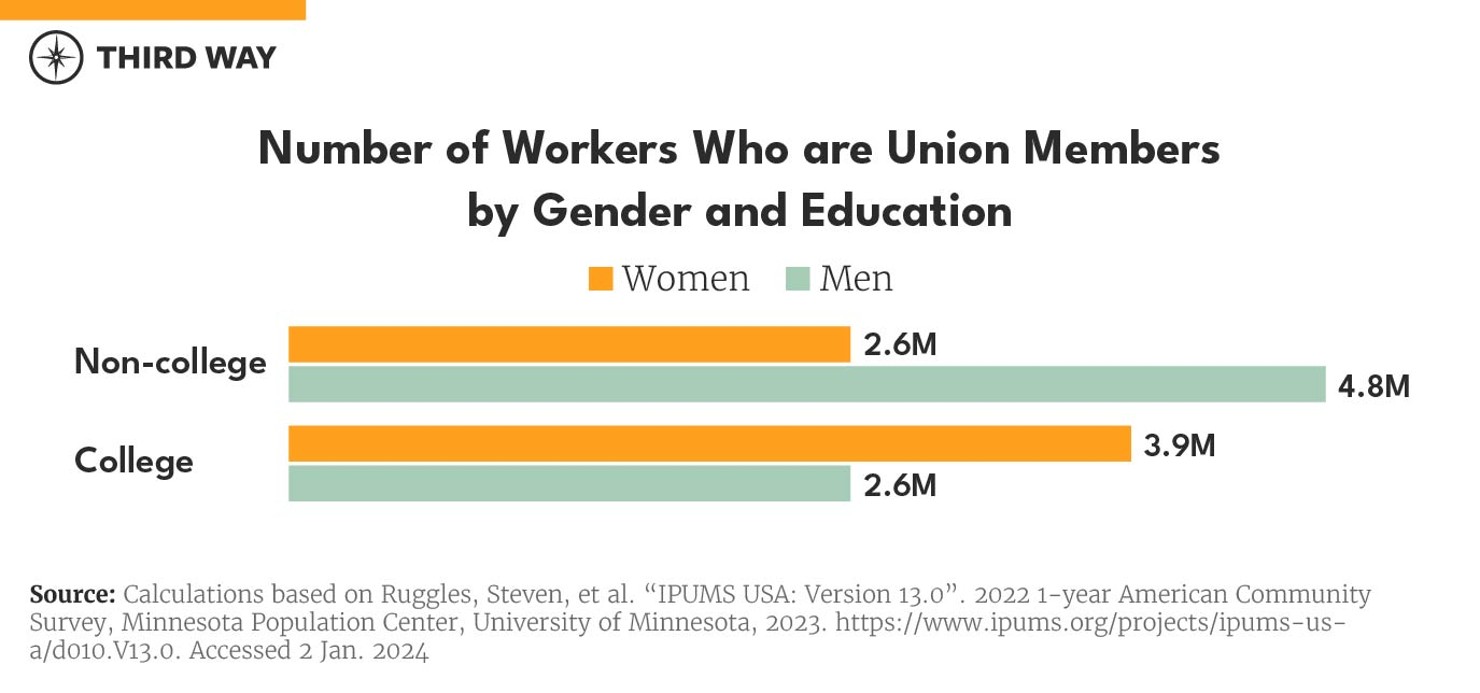

- Just 9% of non-college women are a part of a union compared to 13% of non-college men.

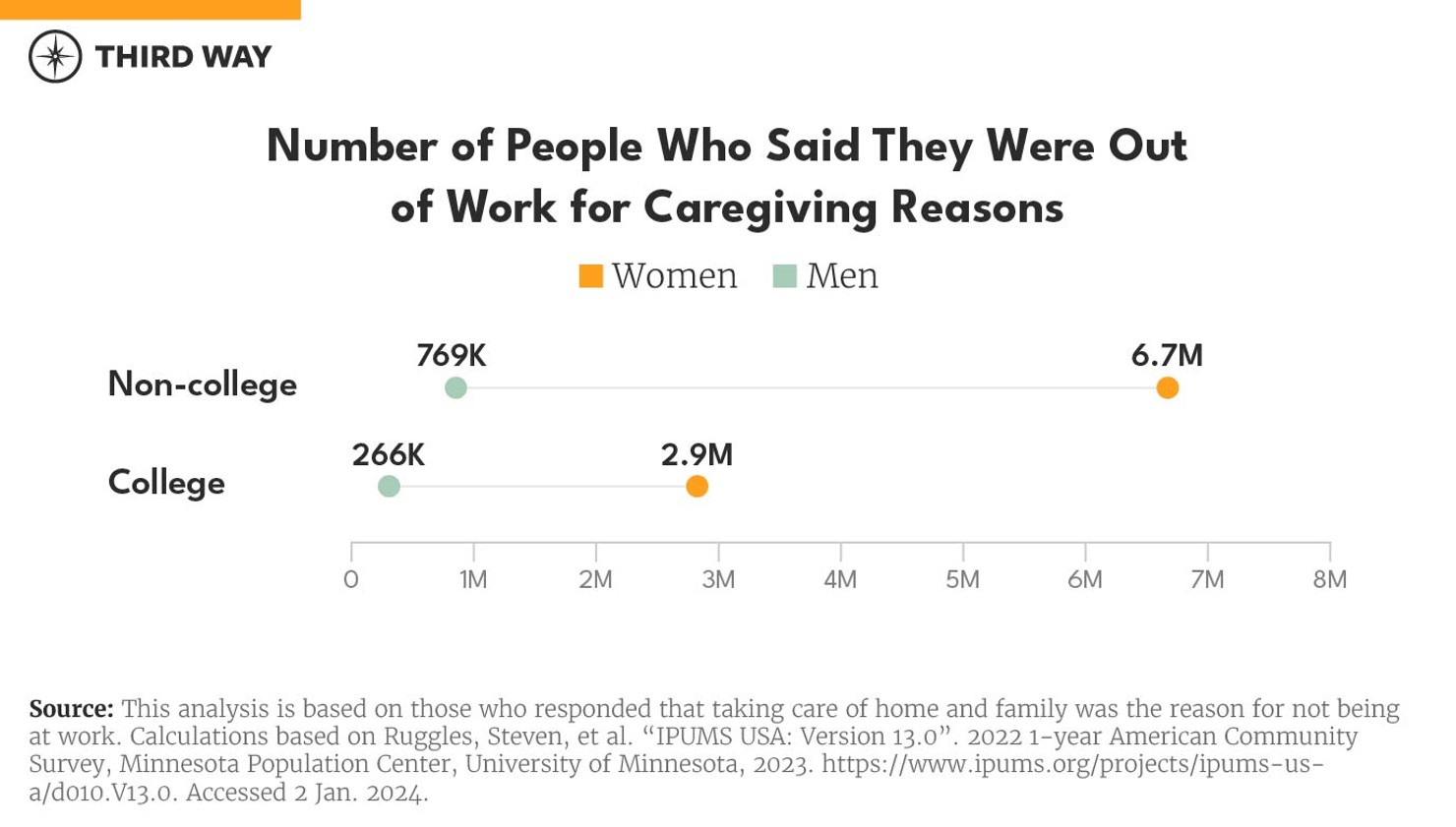

- Non-college women are five times more likely to be out of work for caregiving reasons than non-college men.

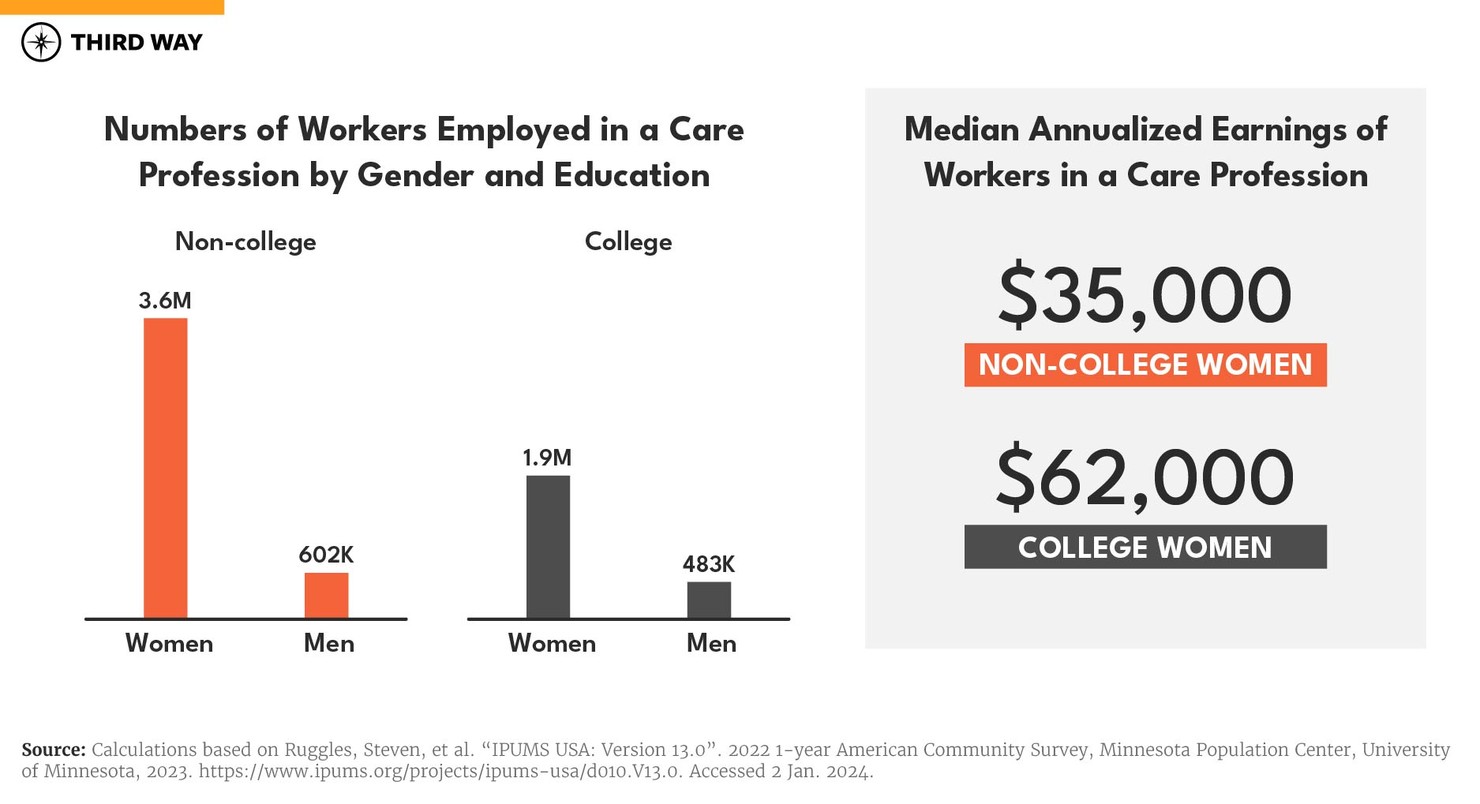

- More than one in ten non-college women work a job where they directly care for others.

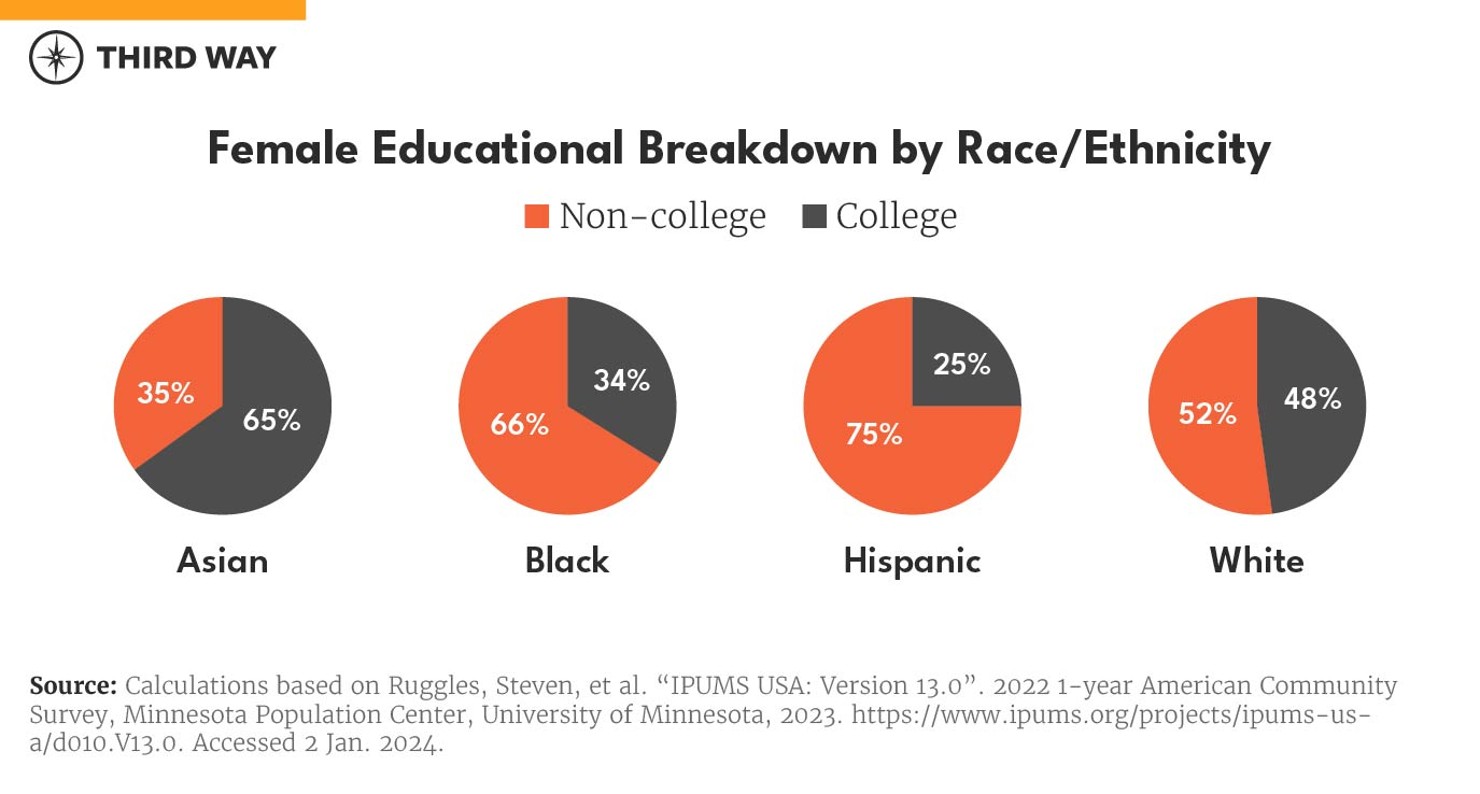

- Half of non-college women are persons of color.

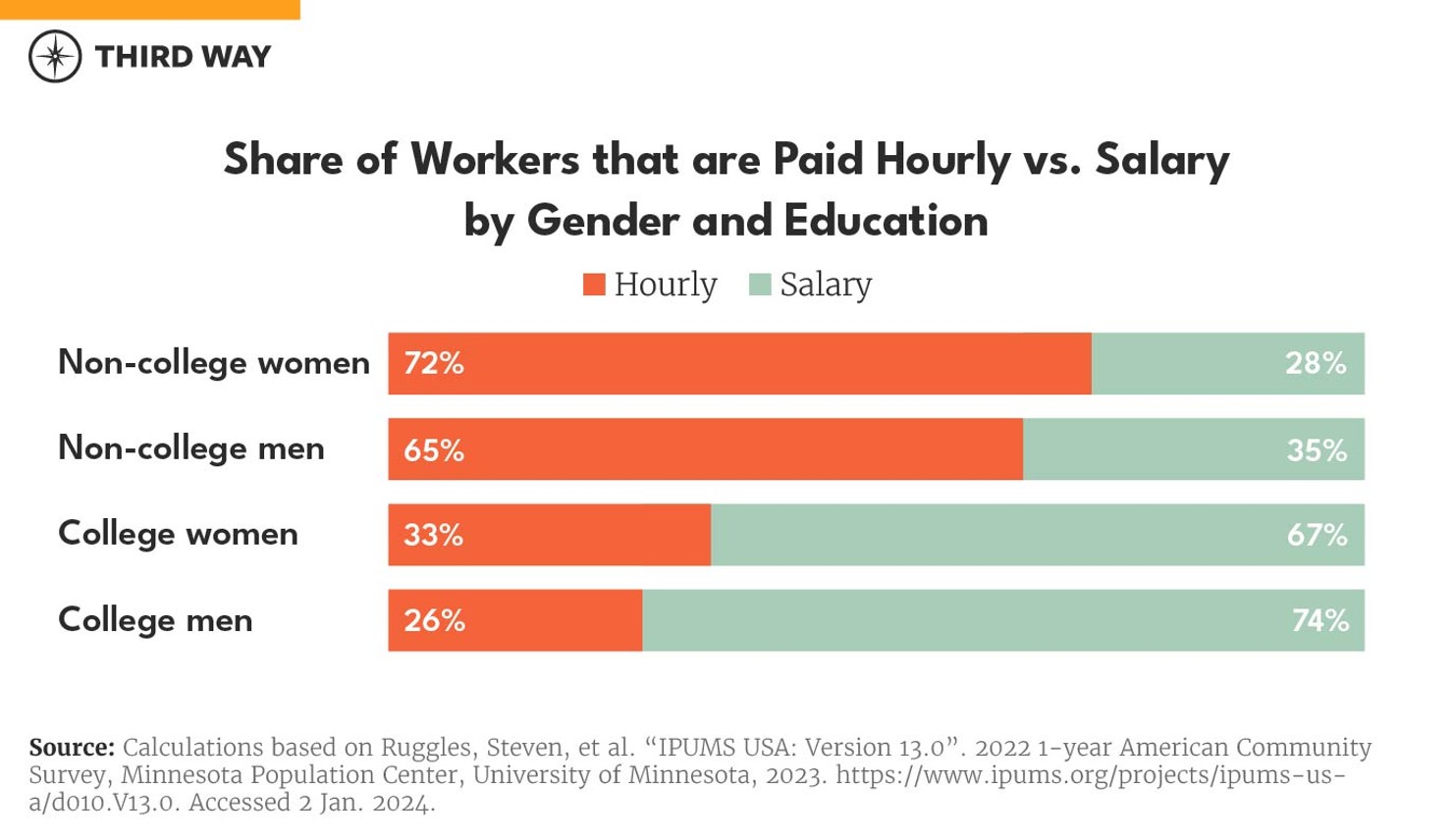

- Three-fourths of non-college women are paid hourly.

The economic realities of workers with and without a college degree are worlds apart, but women without a degree are the ones closest to the economic edge. Just half of non-college women of working age are employed full time. They are over five times as likely as their male counterparts to be out of work for caregiving reasons, and they earn a third less.1 Non-college women shoulder much of our country’s care needs both at work and at home. But our economy isn’t caring for them back.

Meanwhile, many roles that were once reliable pathways to the middle class for non-college women, especially in administrative and sales fields, are disappearing. Big investments in clean energy, manufacturing, and infrastructure will create a surge in well-paying jobs that don’t require a bachelor’s degree, but men stand to benefit the most under current trends. Right now, men make up 90% of construction workers, 98% of electricians, and 68% of those in manufacturing jobs.2

Altogether, this paints a picture of a group teetering on the edge of economic crisis. Below, we highlight the economic situation of non-college women aged 25 to 64, the ages of people most likely to be in the workforce.

Out of the Workforce

Only half of working age non-college women are employed full time.

Much of the narrative around the decline of opportunity for non-college workers has been centered on non-college men and their absence from the labor force. But there are nearly 6 million more non-college women than men of working age that are not employed at all.3 On top of that, women are more likely to work part time. Taken together, only one out of every two non-college women works full time—significantly less than the 70% of men without a college degree and of women with a degree.4

There are a multitude of economic and personal reasons why this is the case. First, for women without a degree, they are overrepresented in sectors where there are significantly fewer options for good-paying jobs.5 While non-college men have long found opportunities in fields like manufacturing and construction, good-paying occupations for non-college women are shrinking fast.6 And on top of that, the jobs where non-college women work are much less likely to turn into long-term careers.7 This leaves many women choosing between lower-paying roles or pursuing a college degree in hopes of getting a higher-paying job. Pew Research finds that women are six percentage points more likely than men to say they need a college degree to get the job they want.8

Caregiving responsibilities also disproportionately fall on women, meaning they are more likely to reduce their hours or leave the workforce altogether to care for children or other loved ones.9 And while providing care is something women with and without degrees both do, there seems to be an outsized impact on non-college women when it comes to the scheduling effects. Around 6.3 million non-college women of working-age work part time, compared to 4 million college women and 3.7 million non-college men.10

Research from the Bureau of Labor Statistics finds that mothers who worked part time saw lower wages, received fewer benefits like paid leave, and got shorter notice on their work schedules.11 On top of that, women without a degree are also more likely to be breadwinners than their college-educated peers, meaning their families are incredibly dependent on their incomes.12 Our analysis finds that across the country, there are nearly 4 million households with children in which non-college women are the sole provider.13

Smaller Paychecks

For non-college women, median earnings are around $35,000 a year, 30% lower than non-college men.

Non-college women earn significantly less than their male peers. The median earnings of non-college men are around $50,000 a year, much more than the $35,000 working non-college women earn.14 The gap is even larger when it comes to men with a college degree—they earn over 2.5 times what non-college women make in a year.15

Many well-paying jobs for workers without a college degree require either certificates, credentials, or some level of skills training. These postsecondary programs help workers gain skills they need after high school or provide them with a stepping stone towards further education. Yet, compared to men, women see less of a return on their investment in job training programs.16 For female high school graduates, certificates offer a wage premium of 16%, significantly less than the 27% increase in wages it provides their male peers.17

The type of jobs non-college women work also contributes to the divide between their incomes. The shifting job landscape is pushing good middle-wage jobs further out of reach for non-college women who increasingly see themselves shunted into lower-wage work.18 For decades, jobs in the office and administrative fields provided non-college women with a reliable path to the middle class. Yet, technological advances, alongside the changing nature of office work, has shrunk many of the administrative positions held by women. As a result, non-college women are expected to bear the brunt of middle-wage job losses in the future—which may further widen the income gap between non-college women and men.19

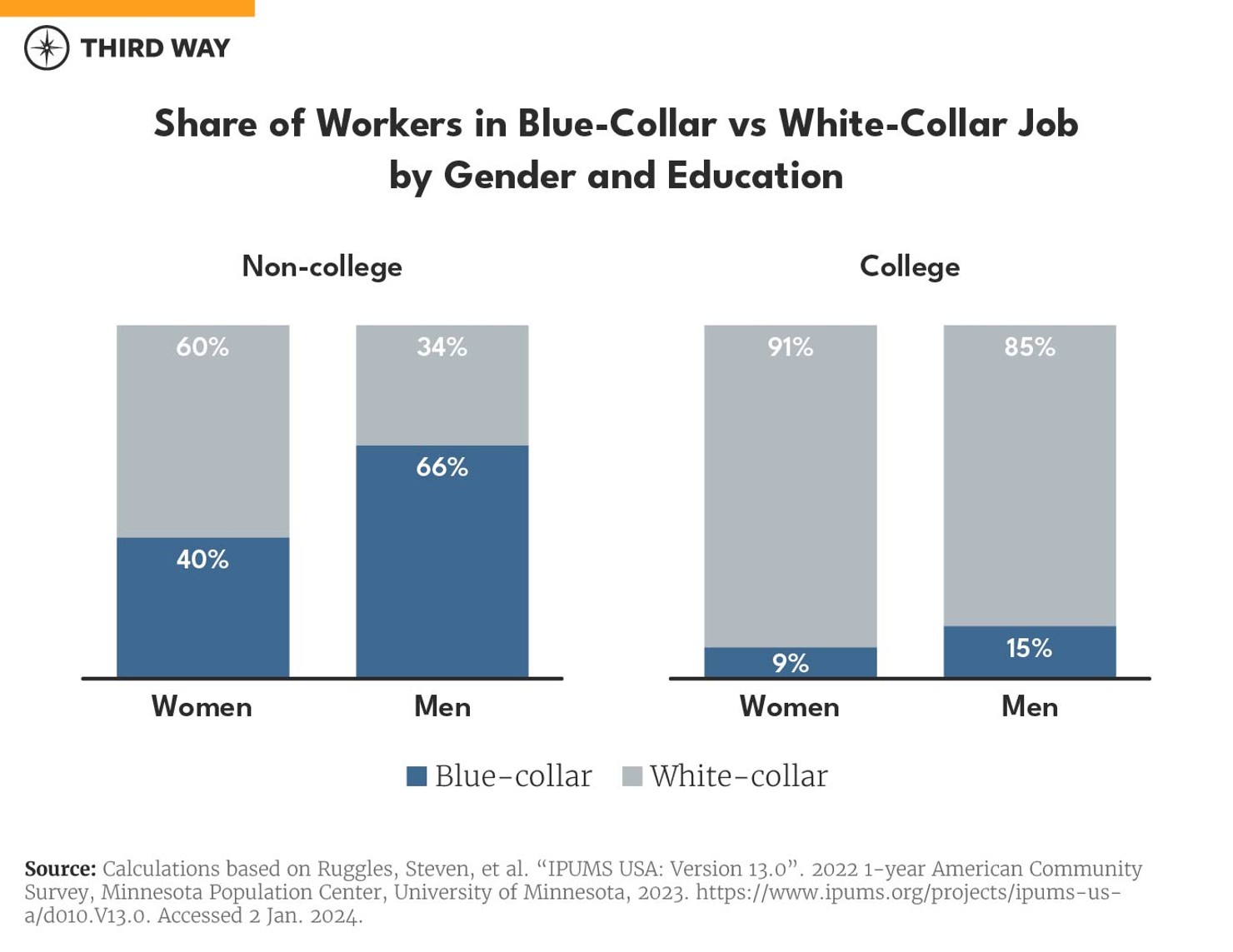

At the same time, investments in manufacturing, infrastructure, and clean energy are creating a surge of new jobs. But men are the ones standing to benefit the most. Considering nearly two-thirds of men without a college degree hold a blue-collar job—compared to 40% of non-college women—it is clear that more support and investment will be needed to get non-college women into these professions.20

Less Union Representation

Just 9% of non-college women are a part of a union compared to 13% of non-college men.

Men without a degree are more likely to be a part of a union than their female peers. There are 4.9 million non-college men in unions, compared to just 2.6 million non-college women.21

This divide is in large part due to the differences in where non-college men and women work. Non-college men are more likely to be concentrated in industries with significant union representation, such as transportation or the trades. Meanwhile, non-college women are more likely to be in occupations with lower rates of union coverage, like the services sectors.22

Interestingly, women with a degree have higher rates of union membership than their male counterparts. High rates of union coverage in the education and health sectors of the economy mean many college-educated women benefit from the support a union provides.23 Women in a union are more likely to see higher wages, face a lower gender pay gap, and receive key benefits like health insurance and pension plans.24

Caring at Home

Non-college women are five times more likely to be out of work for caregiving reasons than non-college men.

Of the 15 million non-college women of working age who were out of work in March of 2023, over 6 million did not work in 2022 due to caregiving reasons.25

Women disproportionately act as family caregivers, but balancing the demands of working and family is much more difficult for non-college women.26 Women with a college degree are often employed in white-collar jobs, which are more likely to offer access to paid leave, child care benefits, and flexible working environments.27 In contrast, non-college women often work at jobs that are lower paying, have more unpredictable hours, and are less flexible—further shrinking their choices when it comes to paid care options.28 Almost 37% of service or retail employees say they need child care during the weekend compared to just 17% of professional or administrative workers.29

Additionally, non-college women are less likely to be married—while two-thirds of college women of working age are married, only a little over half of non-college women are as well.30 This may mean non-college women are not only more likely to be relied upon as the sole financial provider, but also that they shoulder an even larger portion of their families’ caregiving needs.

Lower wages and more caregiving responsibilities means non-college women are more likely to find themselves coming in and out of the labor force.31 According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, women who did not pursue education beyond a high school diploma or dropped out before graduating left the labor force at higher rates than their male peers between 2000 and 2015.32 The disproportionate impact caregiving responsibilities have on women without a degree became even clearer during the pandemic. At the outset, employment declined more for non-college women with children than without, while their job recovery rates have been much slower as well. Employment rates for non-college mothers is still more than 5% lower than in 2020.33

Caring at Work

More than one in ten non-college women work a job where they directly care for others.

Twelve percent of working non-college women are at a job where they provide care to others. In all, 3.7 million women without a degree are in a caring-related job, compared to only 600,000 non-college men.34 While these care jobs are essential to our well-being and economy, they are also some of the lowest paying in our country. Child care workers earn just $28,000 a year while home health aides make a little over $30,000.35

Women of color are overrepresented in care work, especially in the lower-paying parts of the health and child care fields.36 Black women make up over a fourth of workers in the long-term care field, a sector characterized by low wages, limited benefits, and physically demanding conditions.37

The low pay and limited benefits often prevent many of these women from pursuing other job training opportunities or moving up into other jobs.38 The poor quality and wages of these care jobs also pose a huge problem for the future where labor shortages are expected to grow even worse, placing further burdens on working women to provide unpaid care.39

More Diverse

Half of non-college women are persons of color.

Half of working-age women without a degree aren’t white.40 Comparatively, women of color comprise only around a third of those with a college degree.41 Put another way—there are two times as many Black women of working-age without degrees than with one, and for Hispanic women, that number is three times higher.42

Women of color are overrepresented in lower-paying roles, many of which don’t require a college degree. Hispanic women’s share of the low-paid workforce is more than twice their share of the overall workforce, and Black women’s share is 1.5 times larger, according to the Center for American Progress.43 As a result, women of color without a degree are navigating caring for themselves and their families while working roles that offer low wages and very few benefits.

Punching the Clock

Three-fourths of non-college women are paid hourly.

A staggering three-fourths of women without a degree work in a job where they are paid by the hour compared to two-thirds of men without a degree.44 And the number of non-college women working hourly roles is significantly larger than their college-educated peers—there are over two times as many women without a degree working in hourly jobs than women with a degree.45 Salaried workers are more likely to have benefits, retirement options, and see longer-term career success than hourly workers.46

For many non-college women, caregiving responsibilities may factor into their decision to take an hourly job because these types of roles typically allow employees to work fewer hours than salaried positions.47 Research actually finds that mothers are more likely to work in hourly jobs than those without children.48 But working these hourly jobs comes at a cost—less-educated mothers with young children are less likely to have a job than their more educated peers. And when they do return to the workforce, they earn less due to skill depreciation, reduced schedules, and lower hourly wages.49 On top of that, many of the more white-collar (and typically salaried jobs) available to workers with a degree provide a level of flexibility that helps them balance the demands of work and family. But for those in more hourly in-person roles, there is much less of this workplace flexibility and that can make life even harder.50

For many workers, hourly employment does not provide a predictable, routine schedule. Two-thirds of workers in the largest food service and retail businesses in the country see less than two weeks of notice on their schedule.51 Many non-college women work in the service sector, meaning this unpredictability further impacts their ability to work. A lack of insight into when, and how much, one is working can make financial planning, as well as finding child care, all the more difficult.

The unpredictability of many hourly roles, alongside the fact that they offer fewer benefits, limited job security, and reduced opportunities for growth leaves many non-college women on unstable economic ground.

Conclusion

While they often shoulder the burden of care work in this country, non-college women are not being cared for in our economy. They earn less, see greater instability in the workforce, and bear much of the country’s caregiving needs. The lack of opportunity for women without a college degree prevents them from increasing their earnings, pursuing new opportunities, and providing for themselves and their families.

Creating an inclusive economy starts with ensuring all workers are benefiting from rising prosperity. To better support non-college women, policymakers need to focus on an agenda that bolsters pathways for them into male-dominated sectors of the economy, improves the quality of care-economy jobs, and features family friendly policies. This agenda may include efforts such as increasing funding for programs like WANTO which can help close the apprenticeship gender gap, instituting a federal paid family and medical leave program, expanding the child tax credit and making it fully refundable, implementing universal pre-k, and capping costs for child care.

We’d like to acknowledge Joshua Kendall for his contributions to this report. His original analysis of American Community Survey and Current Population Survey data anchors our findings.

Appendix: Methodology

For this report, we used several public use microdata series. First is the 2022 one-year American Community Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau in the 12 months of 2022. Second is the 2023 Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement conducted by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and the U.S. Census Bureau in the three months surrounding March 2023. These two social and economic survey datasets are processed and made available by the Minnesota Population Center at the University of Minnesota (IPUMS).

In each dataset, we made our calculations for four groups of Americans: working age (25-64) men and women with and without a bachelor’s degree. All our counts were derived through the summation of the appropriate survey weights. All calculations were made in R. Code is available upon request from the author.

In our occupational analysis, we sort 2018 U.S. Census Bureau defined occupations into two categories: blue-collar and white-collar. Blue-collar occupations include service occupations; farming, fishing, and forestry occupations; construction and extraction occupations; installation, maintenance, and repair occupations; production occupations; and transportation and material moving occupations. White-collar occupations include management, business, and financial occupations; professional and related occupations; sales and related occupations; and office and administrative support occupations. In addition, care work is defined as non-clergy community and social service occupations, health care support occupations, supervisors of personal care and service workers, child care workers, personal and home care aides, and all other personal care and service workers. These definitions are based on CPS occupation codes.