What We Know About the Cost and Quality of Online Education

The Upshot

The cost and quality of online education have become increasingly popular topics of discussion following the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Over the past two decades, online education has grown considerably and shifted from the margins to become the main source of enrollment growth in American higher education. Although online education is not a new development for colleges and universities, the current crisis has forced nearly every institution in the United States to consider increasing its reliance on online instruction in the upcoming semester and beyond. This policy brief explores what we know about the cost and quality of online education, why high-quality online education is not always cheaper than face-to-face education, and how policymakers can center quality and protect vulnerable students when considering the costs and benefits associated with online education.

Online education can open doors that were once closed for many non-traditional students, but broad access to poorly designed online courses will exacerbate achievement gaps and undermine the fundamental promise of higher education. To that end, this policy brief proposes three recommendations for the federal government: 1) consider widespread distribution and communication of established best practices for providing high-quality online instruction in higher education; 2)require transparent reporting of costs and revenues associated with online courses and exclusively online degree programs; and 3)reinstate regulations to restrict federal aid to institutions providing high-price, low-quality online degree programs.

Narrative

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, colleges throughout the nation were forced to replace face-to-face courses with remote courses in an extremely short period of time during the Spring 2020 semester. Many professors with no experience teaching from a distance attempted to replicate their face-to-face experience and complete the semester by delivering lectures through online video conferencing software. This development brought questions about the cost and quality of online instruction into the national limelight and presented policymakers with a window of opportunity to develop a deeper understanding of online education and consider what protections are needed for college students taking online courses.

To be clear, Spring 2020’s sudden mid-semester shift from face-to-face to emergency remote instruction should not be conflated with online education. Emergency remote instruction is a temporary shift from the faculty member’s planned, in-person instructional method to provide students with immediate access to lectures and course content following a crisis.1 In contrast, high-quality online education requires faculty members to spend a substantial amount of upfront time to design and develop online courses in collaboration with a team of instructional designers, production specialists, multimedia specialists, and other support personnel.2 This brief focuses specifically on the cost and quality of online education, rather than emergency remote instruction, highlighting what we know from prior research about the expense, equity, and effectiveness of online education in higher education.

The Growth and Impact of Online Education

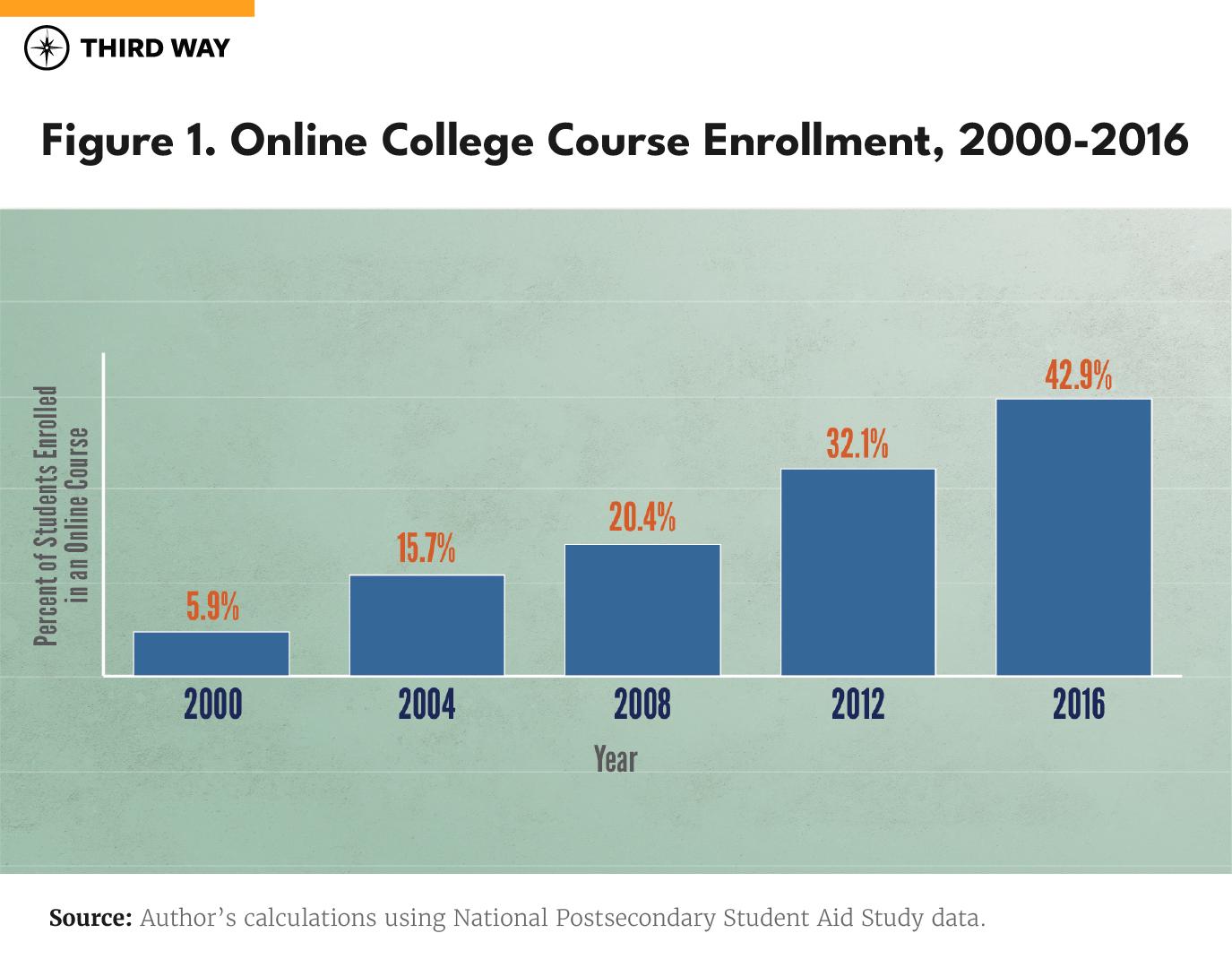

Online education has become an increasingly popular medium of instruction for colleges and universities over the past two decades. The proportion of college students who enrolled in at least one online course has increased from 5.9% in 2000 to 42.9% in 2016.3

As online enrollment continues to grow, face-to-face enrollment has declined in recent years.4 This is due in part to the growing share of college students forgoing the “traditional” college experience and enrolling in exclusively online degree programs. In 2016, 10.5% of college students enrolled in an exclusively online degree program.5

The appeal of online education is clear. Online courses and exclusively online degree programs have the potential to introduce cost efficiencies for institutions and expand access to higher education for many students facing time or location constraints who could not attend college otherwise. Yet the most pressing problem facing proponents of online education is the public’s lack of faith in the quality of online courses—and these concerns are not unfounded.6 Despite the growing prevalence of online education in higher education, colleges continue to struggle with how to offer online courses in ways that can reduce costs and increase revenue without harming quality.

Many researchers have reported that online students earn lower exam scores and course grades than their face-to-face peers enrolled in the same course. Several of those same studies found that Black, Hispanic, and academically underprepared students, in particular, performed significantly worse in online courses than face-to-face courses.7 Surprisingly, many colleges and universities have little guidance regarding how to develop and deliver high-quality online courses as a way to improve the short-term outcomes of their online students.

Despite compelling evidence suggesting that students perform worse in online courses in the short term, a growing body of research has shown that students who enroll in some online courses may also be more likely to persist and graduate when compared to their peers with similar demographic and academic characteristics. For example, research has shown that community college students who enrolled in some online courses during their first year were less likely to drop out, more likely to transfer to a four-year institution, and more likely to earn an associate degree when compared to their peers who enrolled solely in face-to-face courses. More specifically, the estimated odds of dropping out were 17.9% lower for community college students who enrolled in some online courses, and the estimated odds of obtaining an associate degree were 28.8% higher for those same students.8 These findings suggest that online students, many of whom face considerable schedule constraints, can earn additional credits and continue to make progress toward completing their degree by taking some online courses to complement their face-to-face courses.

What Do High-Quality Online Courses Look Like?

Although hundreds of studies have compared the academic outcomes of face-to-face and online students, prior work rarely considers the design of the online courses included in the study. For instance, one experimental study that reported that online instruction has a negative impact on students’ average exam scores made no attempt to offer a high-quality online course and merely posted a weekly recording of the in-person class to the course management software.9

So, what do high-quality online courses look like in practice? We know that high-quality online courses:

- Are guided by instructional designers, who are in-house specialists with training in the development of online courses and the process of online teaching and learning;

- Use shorter videos (i.e., 10-12 minutes) rather than recordings of long face-to-face lectures—any videos longer than 15 minutes should be broken into shorter segments;

- Prioritize faculty-student interaction by providing ongoing and varied feedback, including purposeful discussions to facilitate student learning, limiting each class section to no more than 25 students, and incorporating other activities designed to foster faculty presence and student engagement;

- Identify actionable weekly learning outcomes;

- Remain proactive to ensure students manage their time effectively and take advantage of the institutional support and services made available to them; and

- Evaluate the design and delivery of the online course and incorporate feedback from students into future iterations of the course.10

Public discourse surrounding the cost and consequences of online education often highlights two critical points with direct relevance to federal policymakers. First, students and parents have suggested that online courses should be significantly cheaper than face-to-face courses.11 Second, the quality of online education is considered to be inferior to face-to-face education, which has led to a substantial body of literature in which the academic outcomes of students in face-to-face courses are compared to those in online courses. Here’s the hard truth: The first point can be true, but it reinforces the second point. And actionable steps can be taken to offer high-quality online courses, but those steps are not always cheaper.12

Why Isn’t High-Quality Online Education Necessarily Cheaper than Face-to-Face Education?

For colleges seeking to develop and deliver high-quality online courses, online education is not necessarily cheaper for a variety of reasons. Online students, similar to face-to-face students, benefit from targeted wraparound supports—including low student-to-advisor ratios, tutoring, financial aid assistance, and job placement services—that require substantial investments in personnel unrelated to the design or delivery of a given online course. And the fixed costs associated with developing online courses are actually higher when compared to the fixed costs for face-to-face courses.13 Setting aside the considerable expenses related to technology and course infrastructure, the design and development of online courses require faculty members to work with a team of instructional designers, production specialists, multimedia specialists, and other support personnel to create video lectures, animations, interactive tutorials, and more. Once the online course is developed, however, the variable costs associated with providing the same online course in future semesters can be much lower than the variable costs of face-to-face education.

Online education can open doors that were once closed for many working or place-bound individuals who aspire, but may lack the opportunity, to attend college. But broad access to poorly designed online courses will exacerbate already-existing gaps in educational achievement.

The cost structure of online education, which is associated with economies of scale, suggests that the financial advantage of online education occurs when colleges offer online courses at larger enrollment levels. Because online courses are not subject to the same physical space limitations as face-to-face courses, colleges can recoup their initial investment and generate additional revenue by increasing enrollment in online courses to extremely high numbers. Colleges can cut costs when offering online courses by removing enrollment caps and reducing the number of class sections made available to students. Such financially motivated decisions may be harmful to the frequency and quality of faculty-student interactions—which has been demonstrated to have a negative impact on student outcomes—and the overall educational experience.14

Given the complexities and challenges described above, some colleges partner with third-party companies called online program managers (OPMs) to launch and expand their online offerings. While OPMs have the potential to benefit colleges that do not have the in-house infrastructure or expertise required to recruit, market, and offer online education at scale, the revenue splits between colleges and OPMs can be lopsided (to the tune of the OPM receiving well over half of a program’s tuition revenue) and the contracts can be prohibitively long (locking schools into a dangerous reliance on the OPM).15 The inherent problem with outsourcing services related to the academic core to a for-profit vendor is that financial considerations may unduly influence decisions in ways that prioritize shareholders over students and harm educational quality.

Policy Implications

Online education can open doors that were once closed for many working or place-bound individuals who aspire, but may lack the opportunity, to attend college. But broad access to poorly designed online courses will exacerbate already-existing gaps in educational achievement. Online courses without built-in, personalized, and consistent interaction between the faculty member and student require students enrolled in a given online course to rely on a disproportionate level of self-directed learning. Yet prior work has shown that White students and students with higher levels of educational attainment have greater success with self-directed learning than Black students and students with lower levels of educational attainment.16 Given these dynamics, policymakers should ensure that colleges and universities center quality and protect vulnerable students when considering the costs and benefits associated with online education.

Legislators should consider widespread distribution and communication of established best practices for providing high-quality online instruction in higher education. Colleges seeking to increase their reliance on online education would benefit from further Department of Education guidance on best practices when developing and delivering high-quality online courses. The provision of clear, shared, and elevated standards when evaluating the quality of online education represents a critical next step in accreditation.

Policymakers should require transparent reporting of costs and revenues associated with online courses and exclusively online degree programs. The policy goal in requiring transparency is to ensure that public funding and students’ tuition dollars are spent on instruction and student success initiatives rather than exorbitant allocations toward marketing, advertising, and other expenses that don’t directly relate to students’ educational experiences.17 Unfortunately, the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) currently reports marketing and advertising expenditures under the broad category of “student services,” which can be misleading for students and policymakers seeking to better understand the extent to which colleges invest in student success.18 As federal policymakers increase transparent reporting of costs and revenues related to online offerings, particularly exclusively online degree programs, the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) should collect, collate, and provide these financial data to the public.

Legislators should reinstate regulations to restrict federal aid to institutions providing high-price, low-quality online degree programs as evidenced by alumni who are unable to repay their student loans. The promise of online degree programs suggests that students who invest in higher education will be able to graduate in a better position than when they began college. Simply put, colleges offering online degree programs that leave students with a greater chance of defaulting on their student loans than completing their degree should face severe restrictions on their ability to receive federal financial aid. Many of the colleges leaving students in a worse position fail to invest in high-quality instruction and spend the majority of taxpayer dollars on marketing and advertising to recruit more students to enroll in these sub-par online degree programs. By instituting firmer restrictions on aid to low-quality institutions, Congress can put a check on unscrupulous online degree programs and help students identify programs that will better meet their needs and provide a return on their educational investment.

Endnotes

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. EDUCAUSE Review.

Cheslock, J., Ortagus, J., Umbricht, M., & Wymore, J. (2016). The Cost of Producing Higher Education: An exploration of theory, evidence, and institutional policy. In J. Smart (Ed.), Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research (Vol. 31). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Author’s calculations using National Postsecondary Student Aid Study data. Estimates using Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System data for 2012-2018 are consistently lower but only consider online enrollment in the fall semester rather than online enrollment in the fall, spring, and summer semesters.

Ortagus, J. (2017). From the periphery to prominence: An examination of the changing profile of online students in American higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 32, 47-57.

Author’s calculations using National Postsecondary Student Aid Study data.

Bowen, W. G. (2014). Higher education in the digital age. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Figlio, D., Rush, M., & Yin, L. (2013). Is it live or is it internet? Experimental estimates of the effects of online instruction on student learning. Journal of Labor Economics, 31(4), 763-784; Xu, D., & Jaggars, S. S. (2014). Performance gaps between online and face-to-face courses: Differences across types of students and academic subject areas. The Journal of Higher Education, 85(5), 633–659.

Ortagus, J. (2018). National evidence of the impact of first-year online enrollment on postsecondary students’ long-term academic outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 59(8), 1035-1058.

Figlio, D., Rush, M., & Yin, L. (2013). Is it live or is it internet? Experimental estimates of the effects of online instruction on student learning. Journal of Labor Economics, 31(4), 763-784.

Vai, M., & Sosulski, K. Essentials of online course design: A standards-based guide. New York, NY: Routledge.

College Pulse (2020). COVID-19 on campus: The future of learning. Retrieved from drive.google.com/file/d/1CNqdizKKQCj7MZJwOzVUzd3S8GX k9wIm/view.

Ortagus, J., & Derreth, R.T. (2020). “Like having a tiger by the tail”: A qualitative analysis of the provision of online education in higher education. Teachers College Record, 122(2).

Florida Board of Governors (2016). The cost of online education. Retrieved from web.archive.org/web/20190816093106/https://www.flbog.edu/board/office/online/_doc/Cost_of_Online_Education/03a_2016_10_07_ FINAL%20CONTROL_Cost_Data_Report_rev. pdf; North Carolina General Assembly. (2010). Final report to the joint legislative program evaluation oversight committee (Report # 2010-03). Retrieved from www.ncleg.net/PED/ Reports/ documents/DE/DE_Report.pdf.

McPherson, M. S., & Bacow, L. S. (2015). Online higher education: Beyond the hype cycle. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(4), 135-54.

Hall, S., & Dudley, T. (2017). Dear colleges: Take control of your online courses. The Century Foundation. Retrieved from tcf.org/content/ report/dear-colleges-take-control-online-courses/.

Xu, D., & Xu, Y. (2020). The ambivalence about distance learning in higher education: Challenges, opportunities, and policy implications. In J. Smart (Ed.), Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research (Vol. 35). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Hiler, T., Itzkowitz, M., Dimino, M., & Klebs, S. (2020). 10 ways Congress can ensure accountability in COVID-19 relief for higher education. Third Way. Retrieved from www. thirdway.org/memo/10-ways-congress-can-ensure-accountability-in-covid-19-relief-for-higher-education.

Cellini, S., & Chaudhary, L. (2020). Commercials for college? Advertising in higher education. Brookings. Retrieved from www.brookings.edu/research/commercials-for-college-advertising-in-higher-education/.

Subscribe

Get updates whenever new content is added. We'll never share your email with anyone.