Report Published July 13, 2020 · 12 minute read

Why Regional Public Universities are Vulnerable During Recessions and Must be Protected

Cecilia M. Orphan

The Upshot

Missouri Western State University (MWSU), a Regional Public University (RPU) in Saint Joseph, Missouri, recently announced layoffs of 31 instructors and the elimination of dozens of academic majors including art, philosophy, chemistry, history, English, Spanish, political science, and economics.1 While MWSU had already been bracing for cuts due to a $3 million budget deficit, the state legislature’s decision to cut $1.9 million from this year’s appropriations due to COVID-19 made the situation far more dire. Like many RPUs, MWSU has a mission of providing college access and enrolls a large number of low-income and first-generation college students who will be disproportionately affected by these cuts. And like many RPUs, MWSU’s financial precarity predated COVID-19 and was caused by past recessionary cuts and declining enrollments.2

Recent reports indicate that RPUs in states as diverse as California, Colorado, Georgia, Louisiana, Nevada, New Jersey, Oregon, and Wisconsin are facing similar budget challenges as a result of COVID-19, with predictions that many more states will join their ranks.3 While the current crisis is still unfolding and many unknowns remain about the ultimate impacts on state and campus budgets, we can look to prior financial crises to predict what the future might hold for RPUs. This brief shares findings from a case study examining how recessionary budget cuts affected the “anchor institution” mission of four RPUs and offers federal policy recommendations to ensure the financial solvency of RPUs through the current crisis and in the years to come.4

Narrative

RPUs as Anchor Institutions

RPUs are regionally focused public colleges geographically spread throughout the US.5 While flagship universities have notably increased their enrollment of out-of-state students, RPUs remain important postsecondary access points for residents in their states.6 To better understand the impact that the current recessionary cuts due to COVID-19 may have on RPUs, this case study examined four distinct RPUs in a US state that had significantly cut higher education funding during the Great Recession. four universities studied exemplify the RPU anchor institution mission, as all align programming with the unique needs of their students and regions:7

- RPU #1 is a regionally focused Historically Black University with culturally relevant programming for its African American students;

- RPU #2 serves a rural, Appalachian community, offers both associate and bachelor’s degrees, helps underprepared students prepare for college-level classes, and provides low-cost health services to residents;

- RPU #3 enrolls veteran and disabled students and has a fully handicap accessible campus; and

- RPU #4 leverages university resources to address its city’s racial segregation and houses a law school with a focus on civil rights that offers evening and weekend classes for working adults.

Critically, these four RPUs educate 50-90% of their region’s schoolteachers, and two are their region’s largest employers. The rural RPU houses a performing arts center that offers affordable cultural and arts programming to residents and all four RPUs have nursing and other health science programs.8

Like community colleges, RPUs have missions to promote access to postsecondary education for students historically excluded from elite higher education. Three of the RPUs in this study accept 75-100% of applicants, while the regionally focused Historically Black University accepts 57%. On the whole, RPUs enroll larger shares of low-income, veteran, commuter, undocumented, adult, first-generation, and underrepresented minority students than all other four-year postsecondary sectors, and the four RPUs in this study were no exception. As a result, RPUs generate more upward mobility than any other postsecondary sector, making them vital generators of economic equity.9 As these examples show, RPUs are not ivory towers—instead, they are anchor institutions deeply enmeshed in their regions and the lives of their students.

Why RPUs Are Financially Vulnerable

Despite the important anchor institution mission of RPUs, most are financially vulnerable during and after recessions for several reasons.10 While states commonly cut higher education appropriations during a recession, funding is often restored when the recession ends—but the Great Recession was an exception to this trend. Although state appropriations have increased over the last seven years, state higher education funding has not fully rebounded, and in many states has reached only 65% of pre-Recession levels.11 As a result, public colleges have raised tuition, which has affected affordability and increased student debt levels. As states cut higher education funding following the Great Recession, they also changed how funding is allocated in order to encourage institutional performance in improving degree production, with 46 states currently using or considering implementing performance funding models.12 While there is variability across states in the use of performance funding, some states allocate as much as 80-100% of institutional funding using this strategy. For RPUs, the design of performance funding policies matters a great deal. Poorly designed policies can result in RPUs being held to higher expectations for student outcomes without receiving adequate resources to meet those expectations for the populations they serve, as research shows that first-generation and low-income students require additional supports to be successful.13

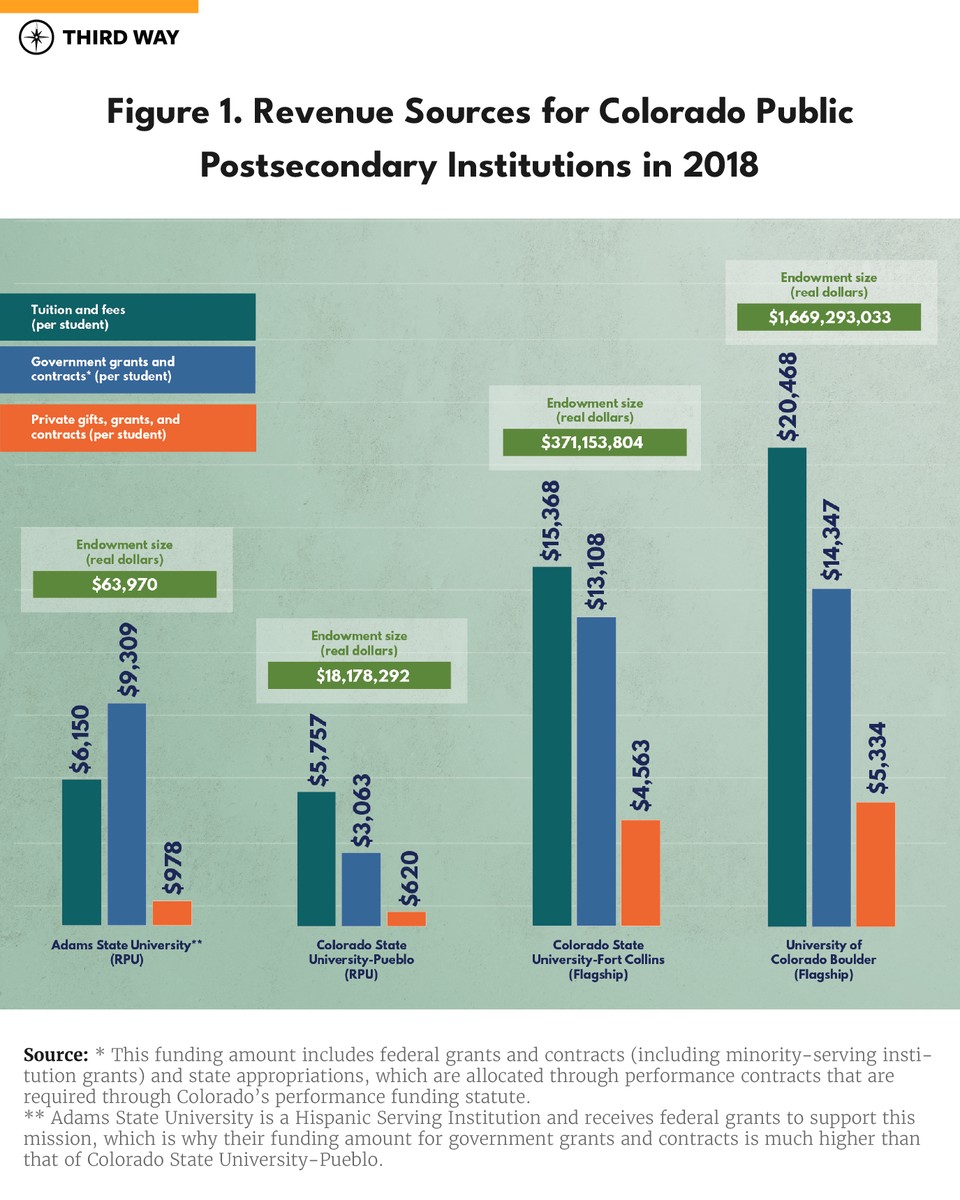

It is also important to note that RPUs have fewer revenue sources than flagships with which to defray recessionary budget cuts.14 Most RPUs have small research operations and are unable to compete for federal research dollars, and they also lack the national or international reputations that would attract out-of-state students. Additionally, many RPUs have smaller alumni bases who are less wealthy, as they educate large shares of schoolteachers, nurses, and other human service professionals, which hinders their ability to fundraise.15 RPUs also have small endowments and reserves relative to flagships. So, while RPUs have become highly efficient institutions due to budget cuts with very little administrative bloat, these very efficiencies mean that RPUs do not have fundraising or advocacy capacity to generate additional revenue.

To demonstrate the differential budget circumstances faced by RPUs and flagships, Figure 1 shows the revenue sources for two RPUs in Colorado, Adams State University and Colorado State University-Pueblo, as compared with the state’s two flagship institutions, University of Colorado Boulder and Colorado State University-Fort Collins. As the figure demonstrates, flagships generate much higher revenue from alternative sources than RPUs and have far larger endowments than RPUs.

How Recessionary Funding Cuts Affected RPUs

The financial challenges described above affected all four of the RPUs in this study. Each RPU is in a state that had severely cut appropriations, necessitating 10-25% reductions to each of the school’s overall budgets, and had also implemented performance funding, which led to a further reduction in their state funding. These financial realities forced institutional leaders to make cuts to campus operations, which impacted their capacity to fulfill their anchor institution missions and provide necessary supports to students.

Impacts to student services: The four RPUs reduced the number of tenure-line faculty and hired additional adjunct faculty, cuts that are relevant to student success as tenure-line faculty yield better long-term outcomes for students than adjuncts. The HBCU cut 60% of its budget for instruction and 63% from its student services budget. The HBCU and one of the other RPUs also cut academic support budgets, with the first cutting 5% and the second cutting 40%. As a result, all four RPUs also increased class sizes and reduced tutoring and academic support services for students. Given that many first-generation students attend under-resourced high schools and require strong academic supports in college, these cuts significantly affected RPU students. Three of the RPUs also instituted or increased parking fees, which posed challenges for low-income commuter students who relied on free or low-cost on-campus parking.

Impacts to postsecondary access: Three of the four RPUs raised admissions requirements in response to the implementation of performance funding, a common unintended consequence of this policy. The risk of funding cuts made it more financially feasible for these RPUs to enroll better-prepared students who need fewer supports than to fully support less-prepared students—introducing a financial incentive that conflicted with these institutions’ historical mission of expanding college access.16 Two RPUs also tried, with limited success, to grow out-of-state enrollments, which negatively affected their regional access missions.

Impacts to regional service mission: All four RPUs increased their emphasis on regional economic development through commercialization efforts, aligning degree programs with regional workforce needs, and creating economic partnerships with other anchor institutions. While these efforts were important to their regions’ economic recovery from the Great Recession, one of the RPUs shuttered its Community Service Center and reduced community outreach services due to budget cuts, and all four reduced community-service funding, which reduced their ability to provide regional service. Finally, three RPUs cut between 9 and 46% of their budgets devoted to public service.

Policy Implications

These findings demonstrate that funding cuts caused by the Great Recession severely impacted the anchor institution mission of RPUs. These impacts could be exacerbated by recessionary cuts due to the current pandemic. COVID-19 budget shocks could also lead to RPU closures and mergers which would curtail postsecondary access nationwide as most people attend colleges within commuting distance of their homes.17 So far, Lincoln University of Missouri and Central Washington University have already declared financial exigency, and the Pennsylvania state higher education system, which governs that state’s RPUs, announced that 700 employees will be placed on leave.18 In Wisconsin, policymakers are planning severe cuts to higher education funding and have required all campuses, with the exception of the two flagships, to review academic programs and determine which to cut—decisions that demonstrate how state policymakers often privilege flagships over RPUs.19

For RPUs in rural communities, layoffs of this kind will exacerbate economic challenges created by COVID-19, as these institutions are often their region’s largest employers. Because RPUs are also incubators of public health talent, awarding 57% of all bachelor’s degrees in healthcare fields, COVID-19 budget constraints could have significant and prolonged public health consequences.20 That’s why any federal COVID-19 higher education response must address the specific needs of RPUs in order to sustain the vital role of these anchor institutions both during this pandemic and for the long-term. This includes:

Ensuring that future stimulus packages better support RPUs. While the CARES Act included student aid for RPU students, it also prioritized full-time enrollment and did not allocate funding to address losses due to student refunds, decreased enrollment, and other COVID-19 related expenses incurred by RPUs.21 Because 48% of commuter and part-time students in the US attend RPUs while balancing familial and work responsibilities, future stimulus packages should remove the full-time student premium.22 The US House of Representatives has taken strides to address this issue by passing the HEROES Act, which removes the full-time enrollment premium and instead awards funding based on student headcount.23 The Senate has yet to vote on this legislation. Additional stimulus packages should also create budget guardrails for RPUs that ensure their ability to provide regional and student services despite COVID-19 budget shocks. Specifically, guardrails should prevent RPU budgets from falling below their 2018-2019 revenues—the year prior to COVID-19 budget shocks. The next stimulus package should also establish block grants for states contingent on their agreement not to reduce postsecondary funding for the duration of the pandemic.

Promoting longer-term financial solvency. Because most states are not constitutionally mandated to fund public colleges and universities, higher education funding is often the balance wheel for state budgets, making public funding unpredictable year-to-year. The federal government can encourage state re-investment in higher education by establishing federal-state partnerships geared at restoring funding to pre-Recession levels.

Supporting rural college access. Currently, 32% RPUs are located in rural regions and these institutions serve largely place-bound populations.24 Just 29.3% of people aged 18-24 in rural areas are enrolled in college as compared with the national average of 42.3%, and 28% of individuals in rural communities hold a postsecondary credential as compared with 41% of those in urban communities.25 To address these college degree attainment gaps and secure the financial wellbeing of rural RPUs following the pandemic, the federal government should create a Rural Serving Institution designation for postsecondary institutions serving rural communities, similar to other designations that exist for schools that serve unique populations like minority-serving institutions and tribal colleges. Such a designation would provide funding for postsecondary institutions that provide a variety of rural-specific services including being the region’s largest employer, addressing rural teacher and health worker shortages, and offering public health and cultural services while providing access to higher education for rural communities.26

While the outlook for RPUs in the pandemic is concerning, these institutions have proven resilient and adaptive over time, having sustained prior budget shocks during recessions. The question is not whether RPUs will survive; the question is what kinds of institutions will emerge from the current crisis and how well these institutions will be able to serve their regions and students. In MWSU’s case, the elimination of liberal arts degrees calls the institution’s status as a university into question and it is likely other RPUs could face similar fates. As anchor institutions, RPUs are vital to state economic and public health recoveries following the pandemic, which is why it is imperative that policymakers act decisively in order to ensure their financial solvency.

Methodology

Case study methods were used in the study described. The four RPUs were in a state in which performance-funding had been implemented and state appropriations had been cut during the Great Recession. Data was collected in 2015 and examined a five-year time period (2010-2015). The author analyzed hundreds of institutional and public policy documents including strategic plans, performance funding allocations, and institutional budgets, and also interviewed 65 individuals including administrators, faculty, staff, and state policymakers. The research described herein was made possible through a grant provided by the New England Resource Center for Higher Education. Additional information about the study’s methods and findings is available at the following endnote.27