Report Published March 26, 2020 · 17 minute read

2020 Reader’s Guide to Understanding the US Cyber Enforcement Architecture and Budget

Anisha Hindocha

Takeaways

The United States is facing a rising cybercrime wave, yet, according to Third Way’s research, less than 1% of malicious cyber actors ever see an arrest. Experts agree that, while there have been positive steps in law enforcement funding needed to close the cyber enforcement gap, the government has not put up adequate funding to meet the demand.

To help Congress understand and evaluate the president’s proposed budget and the agencies involved with closing the enforcement gap, Third Way has prepared an updated Reader’s Guide on the Cyber Enforcement Budget for Members of Congress and their staffs.1

We have included detailed comparisons of enacted amounts for government agencies responsible for cyber enforcement where available for Fiscal Years (FY) 2019 and 2020 and the requested amounts for FY 2021. Congress needs to closely evaluate if these agencies have the resources they need and if the structure of these agencies is most conducive to shrinking the cyber enforcement gap.

Additionally, we provide some detailed recommendations for Congress when moving forward in the appropriations process to boost federal cyber enforcement efforts. These include:

- Increasing the budget and personnel for global cybercrime capacity building led by the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs at the Department of State;

- Requesting a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report to determine if the FBI has enough positions devoted to cybercrime to meet the threat;

- Questioning proposed cuts to the National Computer Forensics Unit (NCFI);

- Ensuring adequate funding for the National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center; and

- Evaluating whether the proposed move of the Secret Service from the Department to Homeland Security to the Department of the Treasury will boost the agency’s ability to investigate cybercrime.

Government efforts to identify, stop, and punish cybercriminals are under-resourced to the magnitude of the threat.

The United States faces a cybercrime wave that affects every sector of the American economy and threatens America’s national security. The threat of cybercrime continues to rise, but law enforcement efforts to identify, stop, and punish the human cyber attackers have fallen short, leading to a cyber enforcement gap.

There are over 300,000 malicious cybercrime incidents reported to the FBI each year, which many, including the FBI, believe is a significant undercount.2 Malicious cybercrime incidents are estimated to cost the US economy anywhere between $57 billion to $109 billion annually.3 Third Way’s research shows that, on average, only 3 in 1,000 of the malicious cyber incidents that occur in the United States annually see an arrest.4 There has been an increase in cyberattacks targeting the healthcare industry and the public as the COVID-19 crisis continues.5 Attorney General William Barr released a memo ordering his deputies to prioritize prosecuting cybercriminals attempting to exploit the crisis, which lead the Department of Justice and Virginia to form a special taskforce aimed at protecting the public from predatory and criminal cyber activities.6

Yet, recent polling shows Americans believe cyberattacks are the number one national security concern and want policymakers to do something to address the threat.7 As public demand for federal law enforcement to close the cyber enforcement gap increases, funding provided by Congress must meet that demand.

Leading experts have argued that more resources are needed from the federal government to strengthen the agencies and departments that have a role in US cyber enforcement efforts. Former FBI General Counsel Jim Baker recently stated on law enforcement action against cybercrime, “It's fair to say enforcement of cybercrime is proportionally low. The missing element is funding at all levels of law enforcement. Society would have to decide to devote a lot more resources to the problem to have another outcome."8 At the same event, former Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for Cybersecurity on the National Security Council, Ari Schwartz, said, “Law enforcement is facing more and more cybersecurity challenges at all levels and needs more resources to do it.”9

It is not just former government officials that believe the resources allocated by the federal government are not enough. Testifying at a budget hearing in 2019, FBI Director Chris Wray said, “Make no mistake, it [the FBI’s cyber mission] is a significant challenge, and it exceeds the bandwidth that we have at the moment.”10 In a recent report for the think tank the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), William Carter and Jennifer Daskal echoed this finding that “Limited resources and disparities in how resources are distributed leave many offices without the tools and resources they need to effectively access and analyze critical information.”11

Without the adequate resourcing current and former government officials and researchers have found necessary, it will continue to be difficult for law enforcement to bring malicious cyber actors, who are taking a toll on the nation’s economy and endangering America’s national security, to justice.

There are numerous key departments and agencies in the federal government with a role in cyber enforcement that deserve further scrutiny in the budget process to make sure they have adequate resources to impact the enforcement gap.

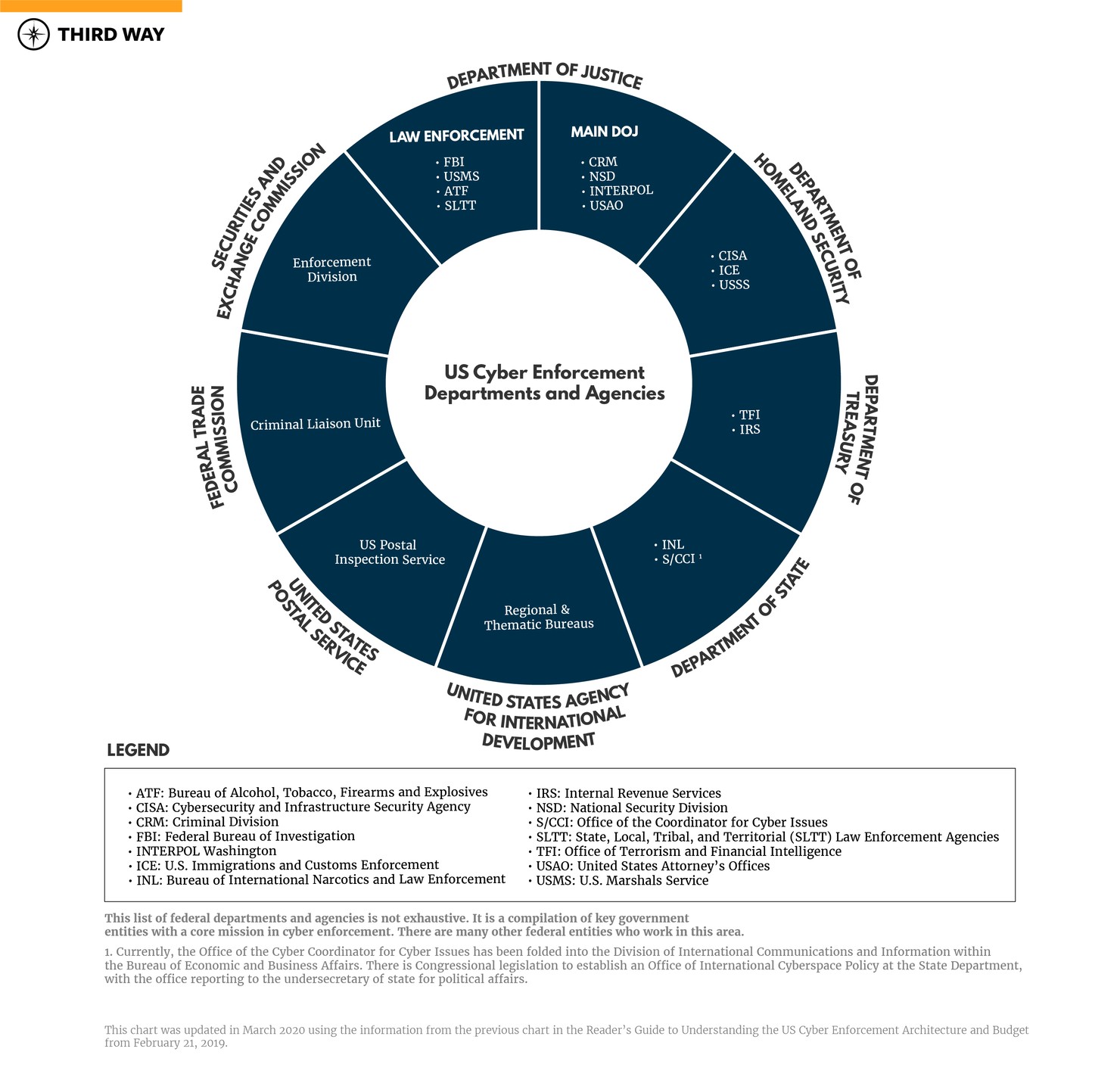

There are eight federal departments and a handful of law enforcement agencies involved in cyber enforcement. As the budget process proceeds, Congress should evaluate whether they have the adequate level of resources to dramatically reduce the cyber enforcement gap. As the US continues to face a cybercrime wave, the current levels of resourcing are clearly not meeting the demand.

The eight federal departments and agencies that have a role in cyber enforcement within the federal government are the Department of Justice, Department of Homeland Security, Department of Treasury, Department of State, United States Agency for International Development, United States Postal Service, Federal Trade Commission, and the Securities and Exchange Commission. A larger discussion of these agencies and departments, and their role in cyber enforcement, can be found in our 2019 Reader’s Guide to Understanding the US Cyber Enforcement Architecture and Budget.12 Additionally, state and local law enforcement agencies also conduct many cybercrime investigations, though these are not largely federally-funded.

The federal government’s current level of resourcing to these entities is clearly not adequate to meet the need and Congress must evaluate whether increases for certain accounts may be necessary to make a bigger dent. Congress has not invested in bringing cybercriminals to justice the same way they have with other foreign threats like terrorism. After 9/11, the FBI took steps to change its priorities to better investigate and address potential terrorist threats including increasing funding for counterterrorism, developing a human capital plan, realigning staff resources to priority areas, and boosting training programs.13 While funding for counterterrorism priorities is critical, the cybercrime wave facing the United States has not been met with a substantial realignment of resources to combat it. In 2017, there were only 1,912 positions within the FBI’s cyber program compared to 13,527 counterterrorism positions.14 Now, the FBI classifies the budget request details for the Cyber Program making it even more difficult to make these head-to-head comparisons. Even though most cyberattacks do not cause the kind of visible, physical, and human impact that terrorist attacks do, the pervasiveness of these attacks, the range of impacts, and the scope of vulnerability is much broader. And without empowering law enforcement and our nation’s diplomats to increasingly pursue cybercriminals, the massive and dangerous enforcement gap that exists will continue while these criminals act with impunity.15

Additionally, when evaluating the FY 2021 budget, Congress needs to assess whether the budget’s proposed move of the US Secret Service, currently housed at the Department of Homeland Security, to the Treasury Department will improve its ability to investigate cybercrime.16 The US Secret Service serves a dual-mission of protection of the president and other key elected officials and candidates as well as criminal investigations, which include financial and computer-based crimes.17 The President’s FY 2021 budget proposes returning the Secret Service to the Treasury Department, where it was based until 2003, because the “increasing interconnectedness of the international financial marketplace have resulted in more complex criminal organizations and revealed stronger links between financial and electronic crimes and the financing of terrorists and rogue state actors.”18 The Treasury Department is home to a number of entities that conduct financial investigations and protect the financial systems, which aligns with the investigatory work of the Secret Service on financial and computer-based crimes.19 However, when evaluating this proposal, Congress should question the Administration on how such a move of the US Secret Service will boost its cybercrime investigatory capabilities and what further investments the Administration intends to make to help in these efforts.

Congress needs to evaluate if key cyber enforcement entities have the necessary funds to make progress to close the cyber enforcement gap.

In order to make progress toward identifying, stopping, and bringing to justice malicious cyber actors, Congress needs to evaluate whether key federal entities with responsibilities related to cyber enforcement have the required funding they need.

In order to aid Members of Congress and their staffs in making this evaluation during the FY 2021 budget process, Third Way has compiled the enacted and requested budgets for key entities within the Departments of Justice, Homeland Security, Treasury, and State that work on cyber enforcement (based on publicly available budget data). In some cases, the entirety of specific divisions or offices are referenced when specific cyber funding is not denoted in the budget.

Department of Justice

The Department of Justice is the main law enforcement agency of the United States. It leads the government’s efforts to prosecute cybercrime through its Criminal Division, National Security Division, and Office of the United States Attorneys, and to investigate cybercrime through its law enforcement agencies including the FBI. It also facilitates cooperation between foreign law enforcement jurisdictions in transnational cybercrime cases through its International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL) Washington office.

Criminal Division (CRM)

The relevant sections of the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice to cyber enforcement are the Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Sections (CCIPS), Organized Crime and Gang Section (OCGS), Money Laundering and Asset Recovery Section (MLARS), Office of International Affairs (OIA), Office of Overseas Prosecutorial Development Assistance and Training (OPDAT), and International Criminal Investigative Training Assistance Program (ICITAP).

National Security Division (NSD)

The relevant sections of the National Security Division to cyber enforcement are the National Security Cyber Specialists (NSCS), Counterintelligence and Export Control Section (CES), and Counterterrorism Section (CTS).

INTERPOL Washington

The relevant sections of INTERPOL Washington to cyber enforcement are the Operations Division and the Office of the General Counsel.

US Marshals Service (USMS), Fugitive Apprehension

The relevant sections of the US Marshals Service to cyber enforcement are the Fugitive Apprehension Decision Unit and Asset Forfeiture Program.

*20**21

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)

The relevant sections of the FBI to cyber enforcement are the Criminal, Cyber, Response, and Services Branch, which includes the Cyber Division and the International Operations Division and the Science and Technology Branch which contains the Operational Technology Division.

The details for the FBI’s Cyber Program budget request are classified in the FY 2021 budget request, as they were for FY 2020, but not prior. The publicly available CBJ contains a request for an additional 41 Full-time employee (FTE) cyber positions at nearly $40 million dollars.22

Department of Homeland Security

The Department of Homeland Security’s role in the effort to combat cybercrime mainly falls within the jurisdiction of its Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Homeland Security Investigations (HSI). CISA is responsible for protecting the United States’ critical infrastructure from physical and cyber threats by coordinating and collaborating across the government and with private sector organizations. CISA contains the National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center (NCCIC), which serves as the nation’s 24/7 hub for information and as an incident center. HSI investigates criminal activity on or facilitated by the internet. The Department currently oversees the United States Secret Service, which conducts computer and financial crime investigations, though President Trump’s FY 2021 budget includes a proposal to move the Secret Service to the Department of the Treasury.

Department of Treasury

The Treasury Department oversees two offices that play a role in the investigation of cybercrime: the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network and the Criminal Investigations Division of the Internal Revenue Service. The Department also plays a role in administering cyber-related sanctions through the Office of Foreign Asset Control.

Department of State

The Department of State works to build the capacity of global criminal justice systems to investigate and prosecute cybercrime and increase global cooperation toward these efforts. These efforts are primarily coordinated by the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs.

The State Department’s cyber diplomacy functions currently largely sit within the State Department’s Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs. In June 2019, Secretary of State Pompeo transmitted to Congress notification of his intent to establish a new, standalone Bureau within the State Department responsible for cybersecurity and emerging technologies that would be led by an Ambassador-at-Large.23 Congress has not thus far allowed this proposal to move forward, and a separate congressional proposal for the establishment of a similar office placed within a different part of the State Department has been introduced in the House called the “Cyber Diplomacy Act of 2019” (H.R. 739).24 However, funding for Secretary Pompeo’s proposed Bureau has been requested in the State Department’s FY 2021 budget request.

Congress can take a number of steps in the appropriations process to aid key agencies and departments to close the cyber enforcement gap.

Congress has an important role in the appropriations process that can shape the ability for federal law enforcement and diplomats to better combat the cybercrime wave and bring malicious cyber actors to justice. The following recommendations identify a number of priorities Congress should focus on in the FY 2021 appropriations process to provide the resources experts and Americans agree are necessary.

1) Request a GAO study to determine if the number of cyber FTE positions within the FBI is adequate to tackle the cybercrime threat to the United States.

The resourcing from the federal government to identify, catch, and bring to justice malicious cyber actors is far less than the resources given to counter other threats. Even now, the FBI’s request in the FY 2021 budget request of 41 additional FTEs is less than an additional 65 FTEs requested for the Combatting Foreign Threats Program in the same request. In order to better understand the nature of the cybercrime threat and the law enforcement resources needed to combat the cybercrime threat, Congress should request a GAO study of the FBI’s workforce to determine if the Bureau is sufficiently staffed to investigate cybercrime and catch the perpetrators of these acts. This GAO report would inform appropriations decisions in future years to make sure the FBI is fully resourced to tackle cybercrime.

2) Raise questions to the Administration about the resourcing that will be provided to the NCCIC now that it has been folded into CISA at the Homeland Security Department.

The NCCIC serves as the nation’s 24/7 hub for cyber information, technical expertise, and cyber incident response. With the passage of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency Act of 2018, the NCCIC was folded into the newly-created CISA. In CISA’s FY 2021 CBJ, the NCCIC does not have its own line item, making it unclear how much of CISA’s budget will be dedicated to the functions of the NCCIC. During congressional hearings, Congress should question how much of CISA’s budget will be dedicated for the NCCIC and ensure the Homeland Security Appropriations bill specifically dedicates such funding for this entity.

3) Ensure continued levels of funding for the State Department’s cybercrime capacity building led by the International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Bureau and evaluate whether increased resourcing and personnel can be provided.

Cybercrime is largely a transnational threat that knows no borders. Often times, a single cybercrime case can involve the cooperation of many different criminal justice sectors around the globe and it is in the interest of the United States to ensure those criminal justice sectors have the capacity and mechanisms in place to facilitate such cooperation with our country. Third Way and the World Economic Forum have found that there is a need for “governments to increase their resources in cybercrime capacity building and evaluate how to ensure funding for these efforts are closer in line with the funding provided to capacity building efforts to tackle other security threats.”25 The State Department’s budget request for Cyber Crime and IPR is $5 million for FY 2021 while Congress appropriated $10 million to these efforts in FY 2020. During the appropriations process, Congress should provide at least this $10 million in critical capacity building funding through the Cyber Crime and IPR line item within the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, consider increasing the number of FTEs in this Bureau dedicated to cybercrime capacity building to manage this programming, and evaluate whether further increases are needed to ensure cybercrime capacity building is closer in line with the funding for other threats.

4) Question the Administration about cuts to the National Computer Forensics Training Institute.

The Secret Service CBJ for FY 2021 includes a $26 million cut to the NCFI from the FY 2020 enacted $30 million. According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), with a budget of $18.9 million, the NCFI operates at one-third capacity,26 so reducing the funding amount to $4 million could be a large potential detriment to a program meant to train state and local law enforcement, prosecutors, and judges to enhance law enforcement efforts to access and analyze digital evidence, which is critical to bring cybercriminals to justice.27 CSIS estimates it would take $35 million per year for the NCFI to operate at full capacity. Congress should question the Administration about these proposed cuts and, when appropriating, consider restoring funding to this vital program. This recommendation is in line with the “Technology in Criminal Justice Act of 2019” sponsored by Representative Val Demings (D-FL-10), which would have made grants available to the NCFI for further funding.28

5) Question if the Administration’s proposal to move the United States Secret Service from the Department of Homeland Security back to the Department of the Treasury will boost the Secret Service’s cybercrime investigative functions.

The President’s FY 2021 budget includes a proposal to move the Secret Service from the Department of Homeland Security to the Department of the Treasury due to increasing connections between computer and financial crimes and the financing of terrorists and rogue nations. Congress should question if this move will improve the Secret Service’s bandwidth to conduct cybercrime investigations and if the administration plans to invest more in the Secret Service’s ability to do so.

Conclusion

The United States is facing a massive cybercrime wave, and experts agree more funding and resourcing is necessary to strengthen the federal government’s ability to identify, catch, and prosecute malicious cyber actors. There are a multitude of agencies and departments in the federal government that are working toward this goal, alongside state and local law enforcement. As Congress moves forward in the appropriations process for FY 2021, Members should evaluate if the entities working to address the cybercrime threat have enough resources to meet the need and look to increase budgets where necessary to start reducing the cyber enforcement gap. There are a number of specific steps Congress can take now in the appropriations process to move the ball forward in these efforts.