Moving Apart: How Non-College Workers Fare in Urban and Rural America

Takeaways

The college and non-college economic divide impacts workers differently depending on where they live in America. Our report shows:

- The extra earnings urban workers typically get over their rural peers is growing for those with a college degree and shrinking for those without. Over the past decade, the urban wage premium decreased 11% for non-college workers and grew 19% for college-educated workers, meaning the pay gap between city workers and rural workers is widening for those with a college degree and shrinking nearly as fast for those without.

- Low wages and high costs are pushing non-college workers out of cities. In urban counties, non-college workers are making half the wages of their college-educated counterparts in increasingly expensive cities.

- For many urban non-college workers their earnings aren’t keeping up with inflation. In America’s top metro areas, workers with some college courses or an associate’s degree under their belt saw their inflation-adjusted earnings decline by 6% over the last decade.

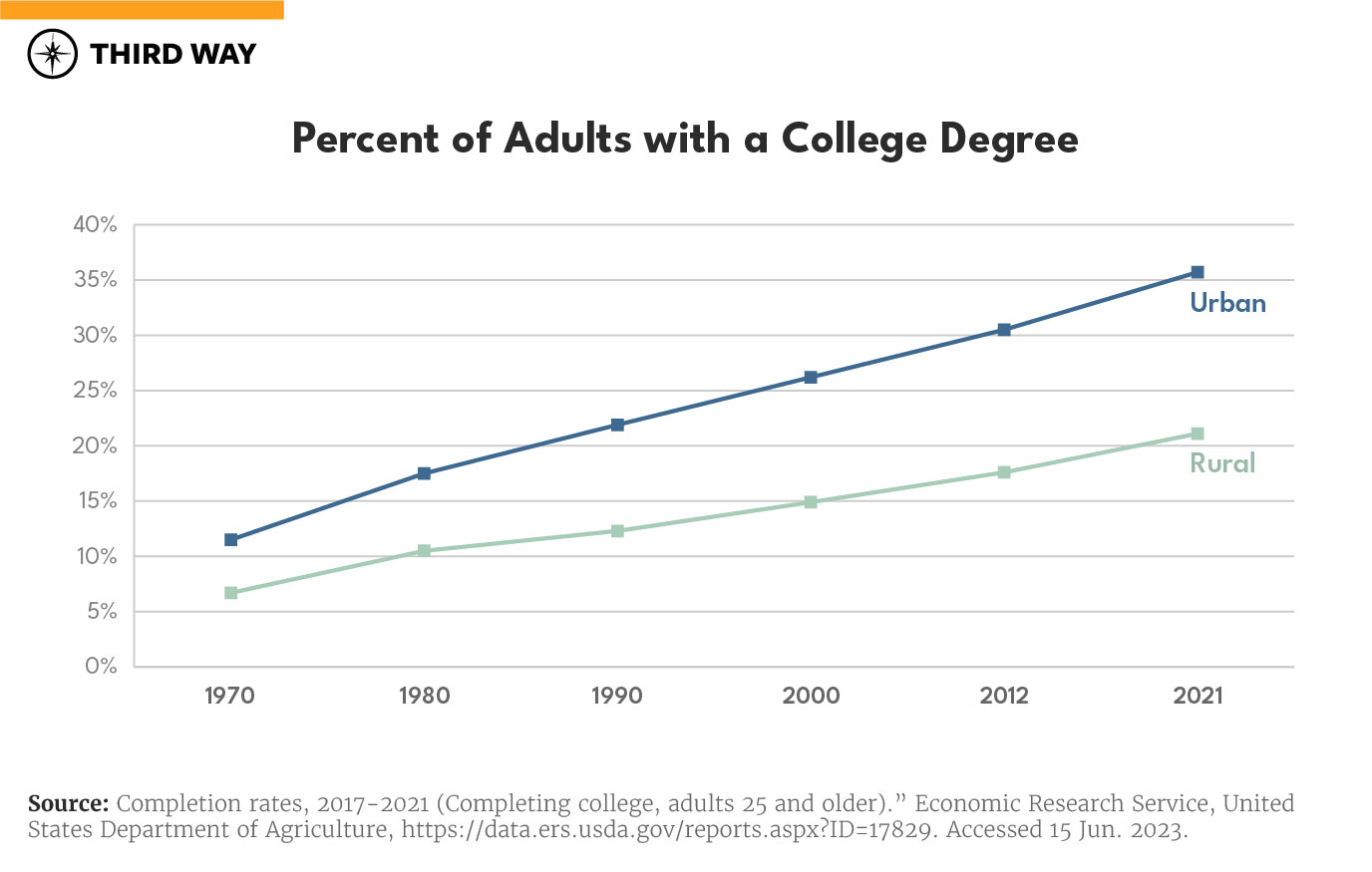

- Rural America is more than thirty years behind urban parts of the country for college education. The percentage of rural America with a college degree today is equal to the percentage of urban America with a college degree in 1990.

- In rural America, workers are much less likely to have a college degree and to be employed. American adults ages 25 - 54 who live in rural areas are 33% less likely to be at work than their urban counterparts.

- Rural places continue to capture only a small sliver of America’s business boom. Between 2012 and 2021, only 1% of the 700,000 net new businesses started in America were in rural counties.

A worker’s educational degree, or lack thereof, drives their economic circumstances—from how much they make to what time they show up to work.1 But so does where they live. Workers without a degree in cities face different challenges from their non-college counterparts in rural areas. In urban places, economic growth has hollowed out middle-class work, leaving fewer good quality jobs available for those without a four-year degree. In rural areas, declining industries and decades of underinvestment have led to a plight of opportunity and a skills mismatch for many non-college workers.

Across both rural and urban America, there are 109 million working-age adults without a four-year degree.2 Below, we unpack how the urban-rural divide is impacting their lives.

Urban Non-College: Driven Down and Driven Out

For decades, workers flocked to cities for good jobs and expansive opportunities. But the economic promise cities once offered has eroded for those without a college degree. Today’s urban non-college workforce is economically worse off than they were in years past. There are a few big reasons why:

Diverging Urban Wage Benefit

Traditionally, urban workers both with and without degrees have earned more than their rural counterparts in the same field of work. Both a lawyer and a janitor living in New York City expect to see higher earnings than their counterparts in rural Ohio.3 But the extra earnings urban non-college workers enjoy over their rural counterparts (also called a wage premium) has steadily been disappearing.4 Between 2011 and 2021, the urban wage premium for non-college workers shrank by 11%, from $3,900 to $3,400, while it grew by 19%, from around $8,200 to $9,700, for college workers.5

Driven Into Lower-Skill Work

The decline in urban wage premiums is largely caused by a dramatic shift in what jobs are available, according to MIT economist David Autor.6 Forty years ago, non-college workers were roughly split between middle-skill jobs (e.g. a factory worker or office administrator, which usually require some sort of credential or training) and lower-skill jobs (which, at most, require a high school degree).7 Urban areas were much more likely to have middle-skill work than suburban or rural places, but economic and technological changes shrunk many of the middle-skill occupations core to urban areas.8 Factory jobs became more automated, office work that used to be done by clerical workers went online, and some labor-intensive jobs were sent overseas.9

Urban college workers in middle-skill jobs were safer from these changes, with many finding opportunity in high-skill industries.10 But the opposite happened for non-college workers—they overwhelmingly got pushed down the occupational ladder into lower-skilled work.11 This polarization of jobs into high-skill and low-skill work also impacted non-college women and men differently. As middle-skill jobs disappeared, women without a degree were more likely to pursue education and shift into high-skill jobs than their male counterparts.12

Autor’s findings that jobs in large cities are increasingly skewed towards either high-skill or low-skill work is further supported by recent census data. In the country’s largest metro areas, the number of workers employed in industries like computer science, mathematics, business, and finance greatly increased between 2011 and 2021, while employment in certain service sector work, such as food preparation, saw moderate increases. At the same time office and administrative jobs, which have historically made up a significant portion of middle-skill work in cities, notably declined.13 And while COVID-19 greatly impacted workers in the services sectors, as well as office occupations, data shows that declines in administrative work was happening before the pandemic even started.14

Can’t Afford Cities—Especially Big Ones

Today, the average median annual earnings for all urban non-college workers is $36,000–much less than the $60,500 for college-educated workers.15 Non-college workers are also three times more likely to live in poverty.16

Lower incomes and rising prices mean over the last decade many urban workers without a college degree saw their earnings decline when accounting for inflation. Almost 50% of the population over 25 in America’s largest cities have a high school diploma but no bachelor’s degree. This group is also more likely to be seeing real declines in earnings.17 Between 2011 and 2021 workers with just a high school diploma saw their real annual earnings decrease on average by almost 2%, from $36,400 to $35,800, while for workers who have some college courses or an associate’s degree under their belt, earnings actually declined almost 6% from $46,300 to $43,600.18

Interestingly during this same period of time workers in big cities who did not graduate high school saw significant increases in earnings, from $25,300 to $28,200. One possible explanation for this trend may be the historic gains low-income workers, especially those in the services sectors, have made in the COVID economy.19 Over this same period, workers with a four-year degree saw their earnings mostly keeping up with inflation. Considering workers with graduate degrees can expect to earn around $88,000, a few hundred dollar decline in real earnings is much less significant than it is for workers with only a high school degree who are earning less than half that.20

This means that bigger, and more expensive, cities remain increasingly unaffordable for many non-college workers. Analysis found that workers with a college-degree enjoy a similar standard of living across most major cities—but for non-college workers, big cities actually mean a worse quality of life.21 Even though San Francisco is a more expensive place to live than Cleveland, the higher incomes allow college workers to maintain a similar type of living, yet for non-college workers earnings are often too low to overcome bigger costs.22

Rising housing prices are a big driver of cities’ unaffordability for non-college workers.23 Previously, both a lawyer and a janitor in New York City would earn more than their counterparts in the rural South, even when accounting for the higher housing costs one finds in cities. Today that is no longer true. The New York lawyer still earns more, but for the janitor, they now actually make less than their rural counterpart.24

The rising costs of housing and everyday goods, alongside fewer options for good-paying jobs, means many without a degree are opting to leave urban areas, either to face long commutes back to the city for work or to not return at all. Since 1980, while college-educated workers have been moving into urban areas, non-college workers are moving out.25 New research also finds that an increasing number of college-educated workers are following non-college workers in leaving the countries’ biggest cities. They are doing so in favor of more affordable mid-sized urban places, which often now offer similar opportunities at a lower cost of living.26

Heavier Burden on People of Color

Non-college America is notably diverse, especially compared to the college-educated workforce. Forty-six percent of the non-college workforce are people of color, and there are three times as many Black and Hispanic individuals without a degree than with one.27 One result of this: the hollowing out of middle-skill jobs, and the poor economic outcomes it causes, has fallen heavily on workers of color.

Between 1980 and 2015, employment in middle-wage jobs declined for white urban non-college workers by 7%, but it dropped 12% and 15% for Black and Hispanic workers respectively.28 This decrease was accompanied by a corresponding increase in employment in low-paying jobs.29 This shift to low-wage work depressed the earnings of non-college workers of color in urban areas—non-college Hispanic workers saw their wage premium in real terms decline by around 6% and non-college Black workers by 14%.30

The physical change in where jobs were located also had poor economic implications for Black urban workers. The movement of jobs from cities to suburbs between 1970 and 2000 was associated with substantial declines in Black employment rates compared to white employment rates.31 While there were many Black workers who moved from the cities to the suburbs and saw increased economic prosperity, those that remained in cities encountered substantially worse economic outcomes. Over the past 50 years, the real incomes of Black suburban workers increased compared to their white neighbors, but Black urban workers actually saw income losses–meaning they were earning comparatively less than before.32

Rural Non-College: Farther from Work and Opportunity

While urban non-college workers find themselves driven down and out, in rural America there is a widening gulf between workers and economic opportunity. The increasing concentration of businesses and innovation in America’s cities, decades of underinvestment in rural places, and the decline of key industries has left rural Americans too far from the tools and opportunities they need to succeed and thrive. Below we unpack these trends.

Lag in Educational Attainment

Over the past 50 years, both urban and rural America have become increasingly educated. But it is happening in urban areas at a much faster pace. Since 1970, the number of adults with bachelor’s degrees increased 24 percentage points in urban counties, and just 14 percentage points in rural counties.33 Today the percent of rural America with a college degree is about the same as the share of urban America with one in 1990.34

In America’s most urban and rural counties, that gap is even wider. Adults living in America’s biggest cities are twice as likely to have a bachelor’s degree as those living in the country’s most remote rural areas.35

This widening educational attainment gap is more layered than just a divide between America’s urban and rural places. Seventy percent of the counties that USDA categorizes as “rural low educational attainment counties” are in areas where Black and Hispanic individuals make up at least 20% of the population.36 Lower educational attainment by communities of color across rural places means they are less likely to reap the economic rewards a college degree offers—rural college workers make 55% more than their non-college peers.37

Opportunity Departs with the College-Educated

After graduating college, many young people from rural communities choose to move to urban centers instead of returning home.38 The pull of opportunity for college graduates to cities has always been there, but the exodus from small towns accelerated as industries like manufacturing saw rapid decline, poverty rates climbed, and rural job growth after the Great Recession was much slower than in cities.39 Meanwhile the growth of opportunity has concentrated in urban places—more rural counties than not have lost businesses in the last decade. And from 2012 to 2021, although the United States added almost 700,000 net new businesses, less than 1% of that growth occurred in rural counties.40

As a result, the exodus of college-educated workers from rural places has further exacerbated the economic struggles of these communities. It increases social segregation, decreases economic growth and innovation, and hollows out resources.41 Without college workers creating businesses and jobs or increasing demand for services, there are even fewer opportunities for those without a degree.

The rise of remote work and the increased movement by workers from cities to rural places is a promising trend. But fostering opportunities for those with and without a four-year degree, and ensuring rural communities have the tools to do so, is essential to the vitality and prosperity of rural places and workers.42

Industry Decline Leads to Labor Force Decline

While the disappearance of urban middle-skill jobs pushed non-college workers into poorer quality jobs, the decline of industries in rural America sent many out of the labor force altogether. Many sectors once key to rural America—such as agriculture, mining, and manufacturing—have dwindled in employment.43 Simultaneously, decades of underinvestment in infrastructure made traveling far distances for a new job difficult, while a lack of access to broadband kept remote jobs or training programs out of workers’ reach.44

And while many rural areas are seeing unemployment rates below pre-pandemic levels, there are still a lot of rural working-age adults who don’t have a job.45 Rural working-age adults are currently 33% more likely to not have worked in the last year than their urban counterparts.46 In rural counties where fewer than 20% of workers have a bachelor’s degree, one-in-four working-age adults did not work at all in the past year.47

The map below shows rural places with a high concentration of adults ages 25 to 54 that did not work in the past year. The high number of prime-age adults out of work across Appalachia, the Black rural South, and tribal lands indicate that place, as well as race and ethnicity, greatly impact the economic outcomes for the rural non-college workforce. Workers across the Black rural South are at increased risk of losing jobs to automation, while Native American workers continue to lose out on remote jobs due to a lack of broadband.48 Minority communities in rural areas also face job discrimination, high rates of poverty, and significant barriers to educational and economic opportunity.49

Training Out of Reach

As employment dropped in manufacturing and agriculture, employment in new sectors such as health and social services increased at a national level.50 But many rural workers don’t necessarily have access to this reallocation of work.51 Many skills training programs remain physically out of reach for rural workers–currently 41 million rural adults live over 25 miles away from the nearest institution of higher learning, while a third of rural workers said reliable access to internet or computer would inhibit them from pursuing a job training program.52 An uncertain job market and cost also prevent rural workers from pursuing more training.53 Without easy access to training programs and the support to pursue them, many rural non-college workers remain out of the labor force or shunted into low-wage work.54

The gap between the skills one has and the skills they need is holding workers and rural economies back from success. A study found over 80,000 middle-skill workers will be needed to fill available jobs in rural California, but only a quarter of nearby educational institutions grant the credentials such work requires.55 And, by 2030, the manufacturing sector could see as many as 2.1 million unfilled positions, mainly because workers won’t hold the digital skills required to do the jobs.56

Conclusion

Huge economic shifts over the past several decades have created significant challenges for the non-college workforce across rural and urban communities. The disappearance of middle-skill jobs in both blue and white-collar industries meant many urban non-college workers ended up in lower paying work. Meanwhile, the decline of industries core to much of rural America’s economy left workers without jobs or skills they needed to succeed. And the continued political treatment of rural America as synonymous with agricultural meant there was a growing divide between the support rural places needed and what they got.57

To be sure, the big investments made in both urban and rural America’s economy in the bipartisan infrastructure law, Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS are critically important in efforts to lift up America’s non-college workforce. But without a clear focus on how to best train workers to meet heightened demand, workers without a four-year degree are at risk of being left behind. To ensure they reap the dividends of economic growth policymakers should focus on improving the quality of low-skill jobs, expanding career pathways to a middle-class life for those without a four-year degree, and increasing support for working families.

Endnotes

Colavito, Anthony, Joshua Kendall and Zach Moller. “Worlds Apart: The Non-College Economy.” Third Way, 19 May 2023, https://www.thirdway.org/report/worlds-apart-the-non-college-economy. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Colavito, Anthony, Joshua Kendall and Zach Moller. “Worlds Apart: The Non-College Economy.” Third Way, 19 May 2023, https://www.thirdway.org/report/worlds-apart-the-non-college-economy. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

McGillis, Jordan. “Remote Work and Urban Wages.” Third Way, 14 Oct. 2022, https://www.city-journal.org/article/remote-work-and-urban-wages. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Autor, David. “Work of the Past, Work of the Future.” Working Paper 25588, National Bureau of Economic Research, Feb. 2019, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w25588/w25588.pdf. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Author’s analysis of American Community 5-year Survey data (2007 to 2011). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; American Community 5-year Survey data (2017 to 2021). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs.

Rural categorizations come from the USDA continuum code. For the purposes of this analysis, non-metropolitan counties are categorized as rural, while metropolitan counties were categorized as non-rural.

Non-college captures workers with less than a bachelor’s degree, while college captures those with at least a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Autor, David. “Work of the Past, Work of the Future.” Working Paper 25588, National Bureau of Economic Research, Feb. 2019, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w25588/w25588.pdf. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Bishop, Bill. “For Those with less Education, Big Cities No Longer Mean Higher Pay.” The Daily Yonder, 13 Jul. 2020, https://dailyyonder.com/for-less-educated-workers-urban-escalator-has-reversed/2020/07/13/. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Autor, David. “Work of the Past, Work of the Future.” Working Paper 25588, National Bureau of Economic Research, Feb. 2019, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w25588/w25588.pdf. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Bishop, Bill. “For Those with less Education, Big Cities No Longer Mean Higher Pay.” The Daily Yonder, 13 Jul. 2020, https://dailyyonder.com/for-less-educated-workers-urban-escalator-has-reversed/2020/07/13/. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Autor, David. “Work of the Past, Work of the Future.” Working Paper 25588, National Bureau of Economic Research, Feb. 2019, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w25588/w25588.pdf. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; Tüzeman, Didem and Jonathan Willis. “The Vanishing Middle: Job Polarization and Workers’ Response to the Decline in Middle-Skill Jobs.” https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Tuzemen-Willis.pdf.

Autor, David. “Work of the Past, Work of the Future.” Working Paper 25588, National Bureau of Economic Research, Feb. 2019, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w25588/w25588.pdf. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Tüzeman, Didem and Jonathan Willis. “The Vanishing Middle: Job Polarization and Workers’ Response to the Decline in Middle-Skill Jobs.” https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Tuzemen-Willis.pdf.

Author’s analysis of American Community 5-year Survey data (2007 to 2011). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; American Community 5-year Survey data (2017 to 2021). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. And; Author’s analysis of American Community 5-year Survey data (2014 to 2019). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; Kopf, Dan. “The loss of middle-skilled jobs is increasing inequality in cities.” Quartz, 17 Jan. 2019, https://qz.com/1523673/the-loss-of-middle-skilled-jobs-is-increasing-inequality-in-cities. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Author’s analysis of American Community 5-year Survey data (2007 to 2011). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; American Community 5-year Survey data (2017 to 2021). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. And; Author’s analysis of American Community 5-year Survey data (2014 to 2019). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Author’s analysis of American Community 5-year Survey data (2007 to 2011). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; American Community 5-year Survey data (2017 to 2021). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs.

Author’s analysis of American Community 5-year Survey data (2007 to 2011). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; American Community 5-year Survey data (2017 to 2021). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs.

Author’s analysis of American Community 5-year Survey data (2007 to 2011). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; American Community 5-year Survey data (2017 to 2021). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. And; Consumer Price Index, Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/cpi/. Accessed 15 Ju. 2023.

CPI data for each metro area was used to calculate the real median earnings of each group of workers in 2021 inflation-adjusted dollars.

Author’s analysis of American Community 5-year Survey data (2007 to 2011). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; American Community 5-year Survey data (2017 to 2021). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. And; Consumer Price Index, Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/cpi/. Accessed 15 Ju. 2023.

Guida, Victoria. “Historic gains: Low-income workers scored in the Covid economy.” POLITICO, 29 May 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/05/29/low-income-wages-employment-00097135. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Author’s analysis of American Community 5-year Survey data (2007 to 2011). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; American Community 5-year Survey data (2017 to 2021). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. And; Consumer Price Index, Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/cpi/. Accessed 15 Ju. 2023.

Moretti, Enrico and Rebecca Diamond. “Geographic differences in standard of living across US cities.” VOX EU Column, CEPR, 17 Mar. 2022, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/geographical-differences-standard-living-across-us-cities. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. This analysis looks at the non-college grouping as those with either a high school degree or some college.

Moretti, Enrico and Rebecca Diamond. “Geographic differences in standard of living across US cities.” VOX EU Column, CEPR, 17 Mar. 2022, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/geographical-differences-standard-living-across-us-cities. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. This analysis looks at the non-college grouping as those with either a high school degree or some college.

Autor, David. “The Faltering Escalator of Urban Opportunity.” Research Brief, Aspen Economic Strategy Group, 8 July 2020, https://www.economicstrategygroup.org/publication/faltering-escalator-of-urban-opportunity. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Ganong, Peter and Daniel Shoag. “Why Has Regional Income Convergence in the U.S. Declined.” July 2017, Working Paper, National Bureau of Economic Research, https://www.nber.org/papers/w23609. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Autor, David. “The Faltering Escalator of Urban Opportunity.” Research Brief, Aspen Economic Strategy Group, 8 July 2020, https://www.economicstrategygroup.org/publication/faltering-escalator-of-urban-opportunity. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; Porter, Eduardo and Guilbert Gates, “Why Workers Without College Degrees are Fleeing Big Cities.” New York Times, 21 May 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/05/21/business/economy/migration-big-cities.html. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; Badger, Emily. “A ‘nationwide gentrification effect’ is segregating us by education.” Washington Post, 11 Jul. 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2014/07/11/college-graduates-are-sorting-themselves-into-cities-increasingly-out-of-reach-of-everyone-else/. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Badger, Emily, Robert Gebelhoff, and Josh Katz. “Coastal Cities Priced Out Low-Wage Workers. Now College Graduates Are Leaving, Too.” The New York Times, 13 May 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/05/15/upshot/migrations-college-super-cities.html. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Colavito, Anthony, Joshua Kendall and Zach Moller. “Worlds Apart: The Non-College Economy.” Third Way, 19 May 2023, https://www.thirdway.org/report/worlds-apart-the-non-college-economy. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Dizikes, Peter. ‘The urban job escalator has stopped moving.” MIT News, 8 Jul. 2020, https://news.mit.edu/2020/urban-job-escalator-stopped-0708. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Autor, David. “The Faltering Escalator of Urban Opportunity.” Research Brief, Aspen Economic Strategy Group, 8 July 2020, https://www.economicstrategygroup.org/publication/faltering-escalator-of-urban-opportunity. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Autor, David. “The Faltering Escalator of Urban Opportunity.” Research Brief, Aspen Economic Strategy Group, 8 July 2020, https://www.economicstrategygroup.org/publication/faltering-escalator-of-urban-opportunity. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Bartik, Alexander W. and Evan Mast. “Black Suburbanization and the Evolution of Spatial Inequality Since 1970.” Working Paper No. 21-355, Upjohn Institute, 15, Oct. 2021, https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/262383. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Bartik, Alexander W. and Evan Mast. “Black Suburbanization and the Evolution of Spatial Inequality Since 1970.” Working Paper No. 21-355, Upjohn Institute, 15, Oct. 2021, https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/262383. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Completion rates, 2017-2021 (Completing college, adults 25 and older).” Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture, https://data.ers.usda.gov/reports.aspx?ID=17829. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

“Completion rates, 2017-2021 (Completing college, adults 25 and older).” Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture, https://data.ers.usda.gov/reports.aspx?ID=17829. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

“Educational Attainment in Rural Areas.” National Center for Education Statistics, Last Updated Oct. 2022, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/lbc/educational-attainment-rural?tid=1000. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

“Rural Education.” Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture, Last updated 23 Apr. 2021, https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/employment-education/rural-education/. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Author’s analysis of American Community 5-year Survey data (2007 to 2011). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; American Community 5-year Survey data (2017 to 2021). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs.

Mahnken, Kevin. “When College Grads Don’t Come Back Home: New Numbers Show a Widening Urban-Rural Education Divide.” The 74, 27 Jun. 2017, https://www.the74million.org/article/when-college-grads-dont-come-back-home-new-numbers-show-a-widening-urban-rural-education-divide/. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; Chinni, Dante. “Rural Youth Chase Big-City Dreams.” The Wall Street Journal, 26 Jun. 2017, https://www.wsj.com/articles/rural-youth-chase-big-city-dreams-1498478401. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Chinni, Dante. “Rural Youth Chase Big-City Dreams.” The Wall Street Journal, 26 Jun. 2017, https://www.wsj.com/articles/rural-youth-chase-big-city-dreams-1498478401. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Author’s analysis of County Business Patterns Tables. (2012). United States Census Bureau, County Business Patterns. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cbp/data/tables.html. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; Author’s analysis of County Business Patterns Tables. (2021). United States Census Bureau, County Business Patterns. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cbp/data/tables.html. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Olmstead, Gracy. “How to keep young people from fleeing small towns for big cities.” The Week, 6 Aug. 2018, https://theweek.com/articles/787958/how-keep-young-people-from-fleeing-small-towns-big-cities. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; “Losing Our Minds: Brain Drain across the United States.” United States Congress Joint Economic Committee, 24 Apr. 2019, https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/2019/4/losing-our-minds-brain-drain-across-the-united-states. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Olmstead, Gracy. “How to keep young people from fleeing small towns for big cities.” The Week, 6 Aug. 2018, https://theweek.com/articles/787958/how-keep-young-people-from-fleeing-small-towns-big-cities. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Low, Sarah A. “Rural Manufacturing Survival and Its Role in the Rural Economy.” Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, 25 Oct. 2017, https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2017/october/rural-manufacturing-survival-and-its-role-in-the-rural-economy/. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; Green, Gary Paul. “Deindustrialization of rural America: Economic restructuring and the rural ghetto.” Local Development & Society, Volume 1, Issue 1. 22 Mar. 2022, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/26883597.2020.1801331. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Haggerty, Mark, Mike Williams, and Lily Roberts. “Build Back Rural: New Investments in Rural Capacity, People, and Innovation.” Center for American Progress, 23 Nov. 2021. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/build-back-rural-new-investments-in-rural-capacity-people-and-innovation/. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; https://www.wri.org/research/benefits-federal-investment-rural-america

Smith, Talmon Joseph. “’I’m in Hot Demand, Baby’: Nebraska Thrives (and Copes) with Low Unemployment.” New York Times, 1 Apr. 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/01/business/economy/nebraska-economy-unemployment-labor.html. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. Author’s analysis of American Community 5-year Survey data (2017 to 2021). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. And; “Full-Time Year-Round Work Status in the Past 12 Months by Age for the Population 16 and over.” United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; “2022 First Quarter U.S. Economic Outlook a Focus on Rural America.” Homestead Funds, 28 Feb, 2022, https://www.homesteadfunds.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Q1-2022-Rural-Economic-Outlook.pdf. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; Board, Conner. “Rural Central Texas counties are seeing their lowest unemployment rates since the pandemic started.” KVUE, 19 Apr. 2022, https://www.kvue.com/article/money/economy/boomtown-2040/rural-central-texas-counties-lowest-unemployment-rate-since-pandemic/269-44043faa-1020-4b55-ba51-367ae2e3e3df. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Author’s analysis of American Community 5-year Survey data (2017 to 2021). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. And; “Full-Time Year-Round Work Status in the Past 12 Months by Age for the Population 16 and over.” United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

For the sake of this analysis prime-age workers are defined as those 25 to 54 years old.

Author’s analysis of American Community 5-year Survey data (2017 to 2021). United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. And; “Full-Time Year-Round Work Status in the Past 12 Months by Age for the Population 16 and over.” United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

“Native American Communities Continue to Face Barriers to Opportunity that Stifle Economic Opportunity.” The Joint Economic Committee Democrats, 13 May 2022, https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/democrats/2022/5/native-american-communities-continue-to-face-barriers-to-opportunity-that-stifle-economic-mobility. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; Pitts, Jacqueline. “Kentucky has too many people without jobs and too many jobs without people, Kentucky Chamber tells legislators.” The Bottom Line News, 27 Aug. 2021, https://kychamberbottomline.com/2021/08/27/kentucky-has-too-many-people-without-jobs-and-too-many-jobs-without-people-kentucky-chamber-tells-legislators/. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; “An Introduction to the Future of Work in the Black Rural South.” Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, 24 Feb. 2020, https://jointcenter.org/an-introduction-to-the-future-of-work-in-the-black-rural-south/. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; Mohr, Caryn. “Native Americans have fewer opportunities to work remotely.” Tribal Business News, 20 Jan. 2023, https://tribalbusinessnews.com/sections/economic-development/14185-cicd-native-remote-work-opportunities. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Shambaugh, Jay, Ryan Nunn and Stacy A. Anderson. “How racial and regional inequality affect economic opportunity.” Brookings, 15 Feb. 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2019/02/15/how-racial-and-regional-inequality-affect-economic-opportunity/. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; Brewer, Graham Lee. “As Native Americans Face Job Discrimination, A tribe Works to Employ Its Own.” Weekend Edition Saturday, NPR, 18 Nov. 2017, https://www.npr.org/2017/11/18/564807229/as-native-americans-face-job-discrimination-a-tribe-works-to-employ-its-own. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; Farrigan, Tracey. “Rural Poverty Has Distinct Regional and Racial Patterns.” Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. 9 Aug. 2021, https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2021/august/rural-poverty-has-distinct-regional-and-racial-patterns/. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Davis, James C. et al. “Rural America at a Glance: 2022 Edition.” Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture, Nov. 2022, https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/105155/eib-246.pdf?v=7004.3. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Haggerty, Mark, Mike Williams, and Lily Roberts. “Build Back Rural: New Investments in Rural Capacity, People, and Innovation.” Center for American Progress, 23 Nov. 2021. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/build-back-rural-new-investments-in-rural-capacity-people-and-innovation/. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

“In rural America, too few roads lead to college success.” Focus Magazine, Lumina Foundation, Fall 2019, https://www.luminafoundation.org/focus-magazine/fall-2019/in-rural-america-too-few-roads-lead-to-college-success/. Accessed 20 Jun. 2023. And; Keily, Tom and Meghan McCann. “Perceptions of Postsecondary Education and Training in Rural Areas.” Education Commission of the States, Jun. 2021, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED613577.pdf. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Keily, Tom and Meghan McCann. “Perceptions of Postsecondary Education and Training in Rural Areas.” Education Commission of the States, Jun. 2021, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED613577.pdf. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

“Many Rural Americans Are Still ‘Left-Behind.’” Fast Focus Research Policy Brief No. 44-2020, Institute for Research on Poverty, Jan. 2020, https://www.irp.wisc.edu/resource/many-rural-americans-are-still-left-behind/. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Rauner, Mary et al. “Supply and Demand for Middle-Skill Occupations in Rural California in 2018-20.” National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, 2020, https://www.wested.org/resources/middle%E2%80%91skill-occupations-in-rural-california-in-2018-20/#. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023.

Wellener, Paul et al. “Creating pathways for tomorrow’s workforce today.” Deloitte Insights, 2 May 2021, https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/manufacturing/manufacturing-industry-diversity.html. Accessed 20 Jun. 2023.

Carey, Liz. “Workforce Issues Compound Financial Troubles for Rural Hospitals.” Daily Yonder, 1 Jun. 2022, https://dailyyonder.com/workforce-issues-compound-financial-troubles-for-rural-hospitals/2022/06/01/. Accessed 15 Jun. 2023. And; Kerlin, Mike et al. “Rural rising: Economic development strategies for America’s heartland.” McKinsey & Company. 30 Mar. 2022, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/rural-rising-economic-development-strategies-for-americas-heartland. Accessed 15 Jun. 2022. And; Buckwalter, Veronica. “’Good Jobs’ in Rural America are Changing, So Learning Must Change Too.” Jobs for the Future, 21 Feb. 2019, https://www.jff.org/what-we-do/impact-stories/accelerating-cte/good-jobs-rural-america-are-changing-so-learning-must-change-too/. Accessed 20 Jun. 2023.

Subscribe

Get updates whenever new content is added. We'll never share your email with anyone.