Report Published December 16, 2015 · Updated December 16, 2015 · 32 minute read

Bundled Payments: A Stable Foundation for Medicare Financing

David Kendall & Jacqueline Garry Lampert

Brian Stickley, a 60-year-old real estate agent in Charlotte, NC, limped due to severe pain in his right knee and gained weight because the pain made him stop taking his daily four mile walk.1 He needed a knee replacement, but that normally would have involved dealing with many different care providers—and a bill from each one. Instead, a Charlotte-based orthopedic practice gave him a “patient navigator” who helped him every step of the way and figured out all of the services he needed—all for one combined price.

A combined price—or bundled payment—gives patients a single price for a given treatment, like a knee replacement. Instead of separate bills for the surgeon, other physicians, the hospital, and physical therapists, Brian received one bill covering his entire episode of care, including rehab. With bundled payments, the provider is accountable for any problems patients might encounter with care because it cannot bill for extra services. And patients are happier with a simpler process and have better outcomes because doctors and the care team use consistent methods to deliver care. If Medicare adopted bundled payments, patients like Brian would receive better care and Medicare would save $206.5 billion over ten years.2

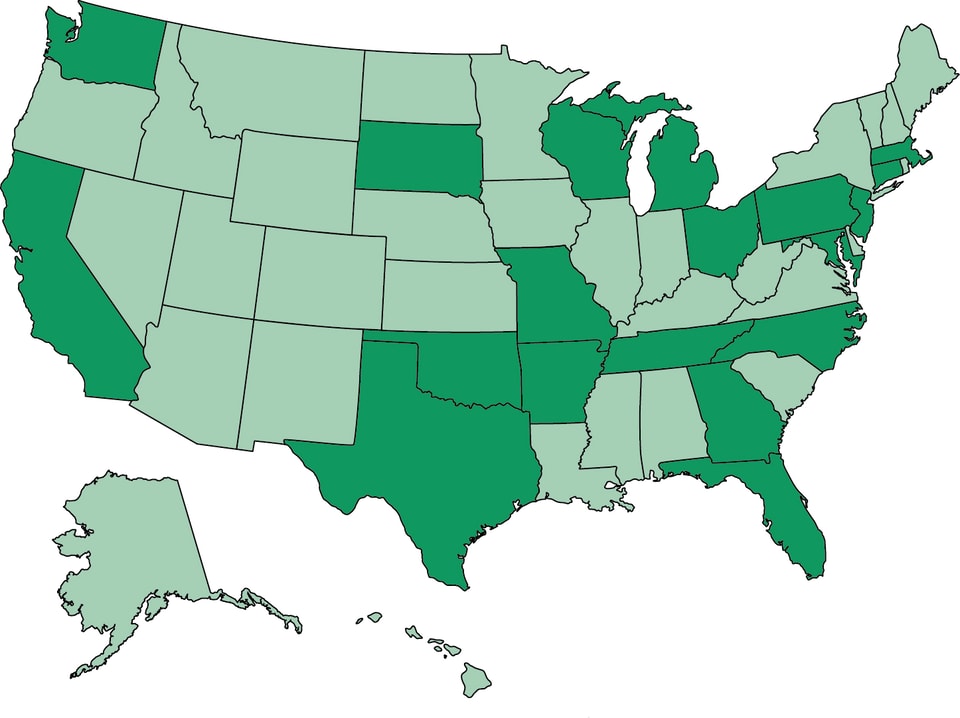

This idea brief is one of a series of Third Way proposals that cuts waste in health care by removing obstacles to quality patient care. This approach directly improves the patient experience—when patients stay healthy, or get better quicker, they need less care. Our proposals come from innovative ideas pioneered by health care professionals and organizations, and show how to scale successful pilots from red and blue states. Together, they make cutting waste a policy agenda instead of a mere slogan.

What is Stopping Patients from Getting Quality Care?

More than half of physician revenue, approximately 53%, is based on à la carte, fee-for-service payments, which incentivize physicians to perform more tasks rather than overseeing a patient’s overall care from beginning to end.3 That has led to substantial, and troubling, variation in price and quality when treating similar conditions. Overall, the fee-for-service model has three major problems.

First, providers get paid more for doing more procedures. For example, every electrocardiogram (ECG) adds a line item to a bill submitted to a health plan. With little health risk or financial downside to patients, it should come as no surprise that ECGs are routine care in hospitals and doctor’s offices—despite professional standards that indicate for most patients they are not necessary.4

Second, providers generally aren’t paid to oversee a patient’s overall care. The original Medicare fee-for-service system encourages providers to operate in silos, paying physicians, hospitals, nursing homes, and others entirely separately—even for their individual parts of the same surgical procedure. This structure “thwarts activities such as care coordination and management of conditions by phone and/or email,” according to an analysis for the Minnesota Medical Association.5 For example, physical therapy prior to a knee or hip replacement can shorten a patient’s recovery time and reduce the cost of care after surgery, as these patients have less need for skilled nursing or home health care.6 But, a surgeon who is not involved throughout the whole process of care, and who has no accountability for a patient’s outcome, may not know if the patient had adequate therapy and will not necessarily make pre-surgical care a priority.

Third, providers have not historically been rewarded for measurable improvement in patient outcomes, giving them little to no incentive to engage in a host of quality-improving activities. A surgeon can perform a technically perfect knee replacement, but that is only one factor in a patient’s outcome. Does one type of knee implant produce a better result than others? Does one surgical team have a lower complication rate from problems like infections than another team? Unless physicians can see how their patients fare overall compared to other physicians, they do not have a full picture about the ways to improve their care.

Because of these three foundational issues, there is wide variation in the quality and cost of care. A seminal study led by the RAND Corporation found that patients receive just 55% of recommended care, on average, with significant variability in care for specific conditions.7 For example, patients received just 10% of recommended care for alcohol dependence but 78% of recommended care for senile cataract, an age-related vision impairment. A more recent study by the Institutes of Medicine (IOM) confirmed what has long been observed by researchers: the fee-for-service model results in extraordinary variation in cost and quality.8 And while Dartmouth Atlas data shows “more than a two-fold variation in per capita Medicare spending in different regions of the country” without an overall effect on quality,9 the IOM study found that such spending variation also occurs at almost every level of measurement—within regions and within hospitals, practices, and individual providers.10

It is easy to dismiss regional variation in health care cost and quality as a ‘wonky’ issue that doesn’t really matter to patient health. The reality is, this variation not only impacts an individual’s health condition, it impacts an individual’s life. The RAND-led study found that just 45% of heart attack patients received beta-blockers, even though they reduce the risk of death by 13% during the first week of treatment and 23% overall.11 And, only 61% of heart attack patients who were candidates for aspirin therapy received it, even though aspirin has been shown to reduce the risk of death from vascular causes by 15%.12 Across the care spectrum—from taking a medical history, to conducting a physical exam, to ordering and reading tests—clinical decisions made by physicians often appear arbitrary and variable. And they are. Physicians reviewing the same information will disagree with each other, and even with themselves, 10-50% of the time.13 This variability suggests that patients may not receive appropriate care when they need it, and they also get low-value care they do not need.14 The fee-for-service payment model, which does not assign accountability for patient outcomes, contributes to this variability by incentivizing providers when they do more procedures, tests, or other billable items.

The impact on patients is not only measured in their health outcomes. Because our health care system is investing money on care patients don’t need, there are no funds to invest in things they do need, like a patient navigator to help chart a course through our complex health care system, or a single, combined, easily-understandable bill.

And yet, this unstable fee-for-service foundation for health care in the United States remains the default payment system. It’s true that Congress, the Administration, states, and the private sector are developing and implementing alternative payment models that move away from fee-for-service and link payments to quality and value. The most significant of all these efforts, the recently-passed Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) incentivizes physicians to participate in alternative payment models, such as accountable care organizations or bundled payments.15 But fee-for-service payments will still remain the default payment system for Medicare providers who do not chose an alternative payment model. Moreover, these new models are built on a fee-for-service foundation. Medicare’s Pioneer accountable care organization model, Shared Savings Program, and Next Generation ACO models all base payment benchmarks on historical fee-for-service expenditures, with various levels of accounting for regional prices.16 Three of four models under the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement program and the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement base payment amounts on historical fee-for-service claims data.17 Payments to Medicare Advantage, which cover 30% of beneficiaries, are also based largely on fee-for-service payments in a region. Even the most aggressive efforts at payment reform will be held back by the weight of the fee-for-service system.

Where Are Innovations Happening?

The innovative concept of “bundled payments” attempts to reward value over volume by offering providers a fee for an episode of care. Often this set fee is a single payment to one provider or organization that is then responsible for compensating the other clinicians who have agreed to work together—rather than Medicare reimbursing unlimited claims from each of them.

Definition: Episode of Care—“a defined set of services delivered by designated providers in specified health care settings, usually delivered within a certain period of time, related to treating a patient’s medical condition or performing a major surgical procedure,” like a knee replacement.18

Bundled payments can save money over the fee-for-service system because the single payment encourages providers to think beyond their own role to the broader quality, value, and coordination of care a patient receives. In other words, instead of conducting a battery of tests (each of which earns the provider a payment under the fee-for-service system), the provider has an incentive to find out which tests have already been performed and not duplicate them. Or, in the case of a bundled payment for surgery, providers have an incentive to coordinate effective pre- and post-operative care, such as checking on implants, coordinating physical therapy, and monitoring each patient’s rehabilitation. Bundled payments demand that providers communicate as cohesive networks and reward the successful treatment of a health problem—not the number of services performed. And they are more convenient for patients, as they receive just one bill for all services related to each episode of their care. Lastly, bundled payments are not new—they have been in place for decades and are in use by payers and providers across the country today.

Dr. Denton Cooley achieved worldwide fame for the first successful implant of an artificial heart.19 He was even more proud of another achievement: the first combined price for medical services.20 In 1984, Cooley and the Texas Heart Institute adopted this radically new approach to medical pricing so Cooley could show how his team was improving the quality of care while lowering costs.21 They set their single fee for a bundle of individual services for coronary artery bypass graft surgery at $13,800, while the average Medicare payment for that same surgery was $24,588.22 Medicare took note and, in the early 1990s, first experimented with bundled payments that combined payments to physicians and hospitals under the Medicare Participating Heart Bypass Center Demonstration.23 Designed to address “worrisome” increases in expenditures on coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery, the demonstration was implemented at seven hospitals for up to five years, and saved about 10% compared to a baseline, while reducing length of stay and maintaining high quality.24 The Ohio State University Hospital in Columbus was one of the original participants and generated $5.4 million in savings while increasing its Medicare bypass market share and improving quality.25 Ohio State continues its involvement in bundled payments, participating in the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement initiative for both CABG and cardiac valve procedures.26

Hillcrest Medical Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma, participated in another Medicare project, the Acute Care Episode (ACE) demonstration.27 During the three-year demonstration, which ended in 2012, Hillcrest improved on several quality measures, such as a lower readmission rate and shorter average length of stay, and reduced the percentage of CABG patients who returned to the operating room during their stay from 7% to 1%.28 In addition, Hillcrest generated substantial savings, largely by reducing spending on implants.29 By standardizing device use and negotiating volume discounts with vendors, Hillcrest saved an average of 10% on cardiac implants (a savings of about $1 million) and 7% on orthopedic implants (a savings of about $450,000). Over the course of the demonstration, Hillcrest reduced Medicare spending by $814 per episode, for total savings of nearly $2.5 million.30 Hillcrest is taking lessons into its participation in Medicare’s Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative.

BPCI, rolled out in August 2011, offers providers a choice of four bundled payment models that expand on the ACE experience. Three of the models include a bundled payment option for 48 episodes of care, which include 180 Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Groups (MS-DRGs) and encompass 70% of all possible Medicare episodic expenditures. As of August 2015, 360 organizations and 1,755 partner organizations are receiving bundled payments across the four models, and Medicare continues to enroll more applicants and study initial outcomes.31

Building on these efforts, in April 2016, Medicare will launch another bundled payment project, the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CCJR) model.32 This effort will bundle Medicare payments for hip and knee replacements, which are among the most common surgeries that Medicare beneficiaries receive. In 2013, these surgeries accounted for 400,000 inpatient procedures and more than $7 billion in hospital spending alone.33 This model is similar in many ways to BPCI, with one notable exception—participation is mandatory for hospitals located in one of 67 randomly selected Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs).34 Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle, Washington, is located in one of the selected MSAs, so participation in the CCJR will be mandatory. However, since 2014, Virginia Mason has received bundled payments for these procedures as one of four providers in the Pacific Business Group on Health’s Employers Center of Excellence Network.35 Like many providers, bundled payments are not a new concept at Virginia Mason.

While Medicare is driving bundled payment experiments on a larger scale, early innovators in the private sector helped launch the movement and are also driving the model forward. For example, planning for the PROMETHEUS (Provider payment Reform for Outcomes, Margins, Evidence, Transparency Hassle-reduction, Excellence, Understandability and Sustainability) payment model began in 2007, and it is used today by health plans and large self-funded employers. Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield of New Jersey developed its “episode of care” programs using algorithms from the PROMETHEUS project.36 Episodes include pregnancy and delivery, colonoscopy, and breast cancer, among others.37 Using PROMETHEUS to expand bundled payments to more episodes of care has allowed Horizon to move from paying for less than 100 bundles in 2010 to more than 8,000 in 2014.38

Another private effort from Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania is the ProvenCare program, which began in 2006 for elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery.39 Geisinger charges a set rate for the surgery, all related services, and any care required within 90 days of the acute stay. The model achieved impressive clinical outcomes, including reduced in-hospital mortality (80%), neurologic and pulmonary complications (40% and 29%, respectively), 30-day readmissions (20%), and average length of stay (8%).40 In addition, both provider and payer benefited financially from the model, with hospital inpatient profit increasing an average of $1,946 per case while payer costs decreased about 5% relative to pre-ProvenCare costs at Geisinger and 28-36% relative to payments to other providers.41 Geisinger has expanded ProvenCare to encompass 17 “service modules” and is participating in Medicare’s BCPI initiative in six episodes of care.42

Some state Medicaid programs are also moving toward bundled payments. In July 2012, the state of Arkansas and its Medicaid program partnered with two dominant commercial insurers to use common bundle definitions and quality measures. Across the state, physicians and hospitals utilize common bundled payment methodologies for more than a dozen episodes of care, including key cost-driving conditions like total joint replacements, congestive heart failure, perinatal care, and asthma treatment. For each episode of care, a “principal accountable provider” is assigned, and providers responsible for particularly efficient and high-quality episodes of care share in savings.43 This work will help prepare providers in Crittenden, Benton, and Garland counties for the bundled payments they will receive for hip and knee replacements starting in April 2016 under Medicare’s Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model.44 In addition, some hospitals in the state participate in Medicare’s Bundled Payment for Care Improvement Initiative, which has similar incentives to the state’s program, and the state received a grant through Medicare’s State Innovation Model to further streamline the state and federal bundled payment models to minimize burden on providers.45 Though studies of private and public payer savings are still underway, the business case for alignment is clear to insurance executives in the state.

How Can We Bring Solutions to Scale?

Over the next 10 years, policymakers should make bundled payments the new foundation for Medicare reimbursement, replacing the current fee-for-service system. To accomplish that, they need to make four changes in Medicare policy:

First, Congress should establish a goal for basing a specific percentage of Medicare fee-for-service payments on bundled payment rates.

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced a goal of moving 30% of fee-for-service payments to alternative payment models, such as accountable care organizations or bundled payment arrangements, by 2016 and 50% by 2018.46 After the announcement of these goals, Congress passed the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act with bipartisan support, which advances the Secretary’s goals by further incentivizing physician participation in alternative payment models. We support Administrative and Congressional action in this area and propose to extend these efforts by making bundled payments the budgetary standard for projecting all Medicare spending that will fall under the bundled payments.

Congress should establish an explicit bundled payment goal by requesting CMS to develop a schedule for developing bundle payment codes over the next several years. Bundled payments take a great deal of effort to develop. They involve not only determining an appropriate combination of individual services, but also setting quality measures to ensure good patient outcomes. Moreover, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) should work with the private sector and state Medicaid programs to ensure as much consistency on the definitions of bundles as possible. CMS could prioritize developing bundles that cover the largest portions of Medicare spending such as sepsis (blood poisoning), osteoarthritis (the loss of cartilage in bone joints), and heart failure. The development of bundles should be a top priority for CMS.

To illustrate how much Medicare spending could be covered under bundles, our analysis finds that bundles for all the patient care for 180 days following a hospital admission would cover 40% of Medicare fee-for-service spending.47

Second, policymakers should direct CMS to use alternative payment models as a cap for payments under fee-for-service.

Medicare’s current efforts in alternative payment models are advancing payment reform. But these efforts will fail to completely sever the connection to and influence of fee-for-service, and they won’t fully address the resulting cost and quality variation across the country.

Part of the reason for this is that Medicare payments under alternative payment models are based on historic fee-for-service claims data. In addition, using historic fee-for-service data to price alternative payment models preserves current behavior patterns and locks in regional variation so that high-cost areas end up with high-cost alternative payments. While Medicare will phase-in a regional cost element to the bundle price for the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement demonstration, this merely addresses variation within nine regions of the U.S., not between the regions—which is where the huge cost differences are. Our proposal addresses this regional variation in Medicare fee-for-service spending by initially basing the price of the bundled payments on a national distribution of current-law fee-for-service spending for the items and services within each bundle. In addition, our proposal addresses some of the regional variation currently built into Medicare Advantage plan rates, because part of the baseline for these payments will include bundled payments rather than being built on a complete fee-for-service baseline.

As noted above, developing bundled payments for the criteria we noted for illustrative purposes would cover 40% of Medicare fee-for-service payments. That amount would create a more stable, but not completely stable, foundation for Medicare. What about the remaining 60% of Medicare payments still based on fee-for-service payments? We propose to make accountable care organization (ACO) payments the baseline for this spending. Unlike the bundles that are tied to a hospitalization, ACO payments cover all the cost of all a patient’s care for a year at time. Finding the right balance between using bundles and ACOs as a cap will be challenging. On the one hand, ACOs provide a more comprehensive foundation for capping fee-for-service because ACOs have an incentive to prevent the use of hospital care by helping people stay healthy and out of the hospital. On the other hand, bundled payments offer greater specificity in capping fee-for-service costs, which helps make sure the payment caps are set fairly in fee-for-service. In other words, having multiple smaller caps through bundles will likely contribute to a more accurate cap based on a lump sum of fee-for-service payments that fall under a bundle. A cap that is split 40-60 between bundles and ACOs would be a good balance if CMS were successful in creating incentives for primary care practices to prevent hospitalizations.

Another challenge in using ACOs as a cap is, if they do not gain a large provider following, their coverage of Medicare cost within a market may not be comprehensive. For that reason, CMS should set a threshold of penetration by ACOs in a given region that would trigger their use as a cap for fee-for-service payments. For example, if the threshold were 25% ACO penetration, then in any region where ACOs are responsible for 25% or more of local Medicare spending, CMS would use ACOs as a cap for fee-for-service cost.

Making alternative payment models the new baseline in Medicare payments would mark a significant shift in Medicare reimbursement policy. It is important to recognize that Medicare has made payment policy changes of this magnitude in the past, such as when payment via diagnosis related groups replaced fee-for-service payments to hospitals. This proposal takes the next logical step in the payment evolution that DRGs began by ensuring that incentives are aligned for all providers involved in a patient’s care. Taken together, this step will make alternative payment model (APM) payments the new foundation for Medicare payments overall.

Third, wherever possible, Medicare should use market-based pricing to set prices for bundles.

Some health care services are “shoppable,” meaning they are typically scheduled in advance, can be performed by many different providers in a market, and have available data on price and quality. An example of a “shoppable” service would be a non-emergency hip or knee replacement. Experts estimate there may be at least 300 of these types of procedures.48 Some health plans and employers are using a strategy called target (or reference) pricing to encourage patients to comparison-shop for the lowest price among providers who offer similar quality care. The target price, which health plans generally set near the average of actual prices, is the maximum coverage that the plan will provide for a service. The health plan member pays any difference between the target price and the price charged by a provider they elect to use.49

Medicare should employ this market-based pricing system for as many “shoppable” bundled payments as possible. Ensuring beneficiaries have access to both quality information on which to base their choice of providers and sufficient choice of high-quality providers in their area is of utmost importance to ensuring the success of this strategy.

Fourth, Medicare should partner with states and private insurers to accelerate the adoption of bundled payments by all patients and payers.

As essential as these changes are, Medicare patients represent only a portion of any provider’s practice. To truly change the care delivery system, and to maximize the associated savings, public and private payers will have to work together. Medicare can help lead this system-wide change.

Like all of us, doctors are creatures of habit. If bundled payments are going to be successful in redesigning care, a physician’s daily routine must change. Behavioral science teaches us that habits only change if practiced consistently and in the same context—so physicians are less likely to get into the habit of communicating with a patient’s physical therapist or relying on someone else’s diagnostic tests if they only do so for some patients but not others. In order for a set of providers to transform the way they work together to coordinate care and reduce duplication, the effort needs to involve all patients. This means private payers need to be involved, too.

MACRA begins this process by recognizing non-Medicare payments as a separate threshold for qualifying for the APM payment pathway—physicians can either receive a certain percentage of Medicare payments or of Medicare and all payer payments via APMs in order to qualify for this pathway. Medicare can continue this work in two ways:

- Require that if practitioners wish to receive bundled payments from Medicare, they must also have similar contracts with other payers, creating a new demand for these contracts in the marketplace.

- Medicare should expand its support for state or regional conversations among payers to align the definitions of their bundles, payment methodologies, and quality metrics—reducing the burden on providers and accelerating clinical transformation.

States are already motivated to participate in such multi-payer activities, as they stand to gain from Medicaid savings. And working with others reduces their upfront costs. But in order to bring other payers to the table and into policy alignment, Congress should empower Medicare to serve as a convener or a participant in collaborations, with funding and loosened regulatory barriers, to allow payers to collaborate with federal and state governments without fear of anti-trust violations.

Potential Savings

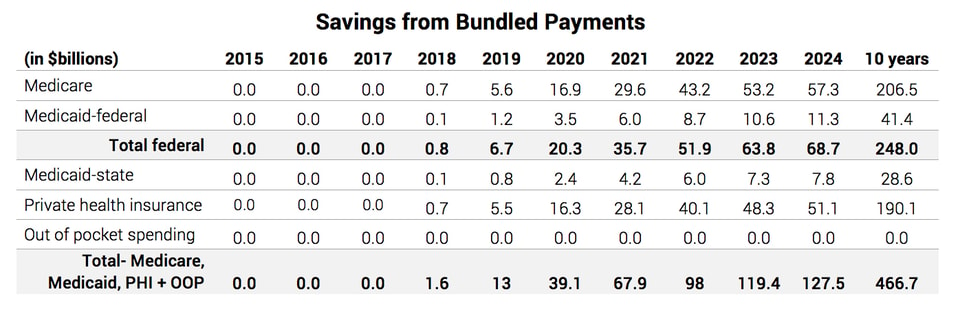

Based on a phased-in approach to implementing bundled payments in Medicare, the ten-year savings would be $206.5 billion.50 The chart below shows the year-by-year savings from the proposal through the health system.

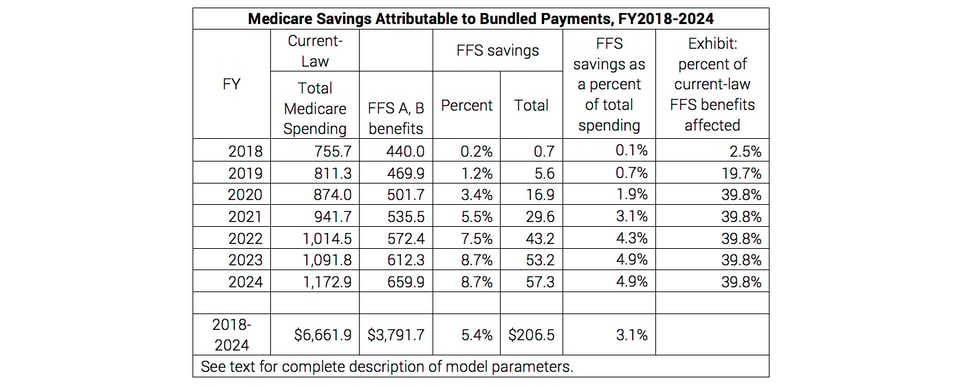

The savings estimate assumes a cap on fee-for-service payments based only on bundles that cover 180 days of care following a hospital admission.51 (Modeling the effect of an ACO cap on Medicare services that do not fall under a bundle payment was beyond the scope of this analysis.) The chart below illustrates how this approach would move an estimated 40% of Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) payments under bundled payments. The savings under this approach would come from reducing the regional variation in the costs of a bundled payment. Providers would also have a strong financial incentive to save money by preventing patient complications, reducing duplicative tests and procedures, and coordinating care to prevent a patient’s health problems from worsening.

Fully implemented, the savings would equal 5.4% of Medicare spending for physician and hospital care in traditional fee-for-service Medicare over ten years. Greater savings could be achieved with a faster implementation schedule. Our analysis utilizes a ten-year phase-in, reducing payments and adding more bundles each year (starting with those that account for the most current-law spending). This approach would eliminate 25% of the regional variation in costs under bundled payments.

Other options for achieving greater savings include extending bundled payments to more health care services (such as chronic care) and tightening caps on regional variation in costs. For example, using market-based pricing for shoppable bundles without any other caps in fee-for-service Medicare would save Medicare $9.1 billion over ten years.52

Other estimates of savings show similar results. For example, RAND estimates that implementing bundled payments for 10 common conditions or procedures* would reduce health care spending in Massachusetts by 5.9%.53

The procedures are: knee replacement, hip replacement, bariatric surgery, acute myocardial infarction, diabetes, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, hypertension, and coronary artery disease.

Questions & Responses

Are hospital and physician costs being bundled today?

Medicare already pays hospitals a bundled payment for the hospital’s portion of a patient’s health care bills. Each hospital payment is called a diagnostic related group (DRG). Medicare adopted this payment system in the 1980s, and it has been credited with saving Medicare money.54 Many private insurance plans have adopted DRGs, saving employers and employees money as well. But a DRG does not include the physicians’ fees, payments to labs, or payments to post-acute providers, such as nursing homes or home health aides, as we propose. These types of more comprehensive bundled payments are being testing in Medicare (e.g., BPCI and the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement) and utilized by private payers across the country.

What does a bundled payment look like?

Under the existing bundled payment system for hospitals, each DRG has its own code. For example, the code for a “heart transplant without complications” is 002.55 Hospitals submit a bill to Medicare based on hundreds of DRG codes. Their payment is for all the hospital’s costs, ranging from the operating room staff to the patient’s stay in the hospital. Physician fees, however, are separate. Under bundled payments, the physician and hospital costs would be paid together in order to encourage the physicians and hospital staff to work together to control costs and improve quality. Similarly, a bundled payment may include payments to practitioners who take care of patients after a hospitalization, such as a nursing home, physical therapist, or home health aide. Some forms of bundled payments give one lump sum to a particular provider to distribute among collaborating peers, other models continue paying individually billed fees but then reconcile payments at the end of the year.

How are bundled payments different from package pricing?

As part of current hospital payment policy, CMS has been packaging the reimbursement for a variety of ancillary services (like lab tests, blood products, and stress test agents) with primary services (like blood transfusions and cardiac diagnostic tests).56 While conceptually similar to a bundled payment, package pricing is fundamentally different in two ways.

First, bundled payments are far more expansive. Under bundles, providers’ actual costs of delivering services for each patient would be averaged over a much wider set of services than under package pricing, which targets a narrow set of services. With a wider set of services, a bundled payment is much more money than a package price, giving providers more flexibility with their resources to customize care for each patient. This flexibility will overcome a big challenge in designing a package price where the fluctuations in costs from patient to patient can be so significant that they create an inappropriate incentive for providers to hold back expensive services that only some patients need. Second, bundled payments, unlike package pricing, will have specific quality measures to accompany the payment. These measures will show whether providers are doing a good job of delivering high-quality care consistently—even as they try to find efficiencies in the use of services.

Doesn’t this proposal favor bundled payments over ACOs?

No, the intention of this proposal is to the use the most practical and effective ways to limit Medicare spending without cutting benefits or reducing the quality of care. While bundled payments are the main focus, we fully support expanding ACOs so they can help limit Medicare spending in ways that bundles cannot. That is not to say the ongoing debate between supporters of bundles and ACOs is not important.57 In our view, no matter which approaches proves more successful, policymakers should use the best of both as a new foundation for Medicare payments.

Is the distinction between bundled payments and ACOs black and white?

No, the distinction in the practical application of the two concepts creates gray areas. For example, a draft white paper from the Healthcare Payment Learning and Action Network, which CMS sponsors, shows how payments for specific disease conditions can at first seem like a bundled payment but instead work more like an ACO for a specific group of patients.58 The differences between the two concepts will remain important, but the potential for further development of each concept might lead to an even stronger foundation for Medicare payments.

What about payments to physicians who see sicker or high-risk patients?

Bundled payments could be adjusted based a physicians’ mix of simple and complicated cases. These adjustments would be similar to the system in place for adjusting payments to hospitals under DRGs. Bundled payments could also be adjusted for other factors known to increase the cost of delivering care, including socioeconomic status. The extra payments for sicker or more complex patients ensure that physicians don’t try to avoid seeing sicker patients who have higher costs for reasons like pre-existing health problems or poor access to regular preventive care.

What ensures that patients will get all the services they need?

Although physicians will have an incentive to reduce the amount of services under a bundle payment, patients can be assured that only unnecessary services will be weeded out for three reasons. First, physicians will have to report on their patients’ outcomes. Quality measures will expose poor performance and protect against the risk of providing too few services under a flat payment. Second, physicians can still face legal recourse from patients if they don’t provide all the necessary care. Third, hospitals and physicians will work as a team to prevent gaps in care that occur when specialists practice alone and no one coordinates a patient’s care.

How will the federal government determine which services should be included in a bundled payment?

The technical work of determining the details of bundled payments has already begun. Medicare administrators are conducting demonstration programs to see how bundled payments can work in practice.59 They will use the results of these programs and an earlier acute care episode demonstration60 to set new payment policies. Given the complexity of the work, it will take time to create all the bundled payments. In the current work, and as more bundled payments are developed, physicians and hospitals have an important role to play. Medicare asked providers to propose the structure of bundles for certain episodes, and then used that input to construct common definitions in BPCI. Specialty organizations and innovative practitioners must remain actively engaged so that the payment incentives align with clinical care.

Is it possible that bundled payments will comprise more or less than 40% of Medicare fee-for-service payments under this proposal?

Yes. Our analysis is based on establishing payment rates for certain acute and post-acute care using bundled payment methodologies. While the criteria are established (hospital admission plus 180 days, not preceded by a hospitalization related to the same organ system during the previous 180 days), and as hospital care utilization patterns shift, the percentage of Medicare fee-for-service payments included in bundles may change.61

Most health plans today don’t come close to covering 40% of spending through bundled payments—how is this even possible?

Our proposal uses bundled payment methodologies to establish the rate for 40% of Medicare fee-for-service payments and builds on HHS’ goal of moving 30% of fee-for-service payments to alternative payment models by 2016 and 50% by 2018.62 To help with the transition, our analysis assumes a 10-year phase-in, reducing payments and adding more bundles each year (starting with those that account for the most current-law spending).

What about outpatient care not related to a hospitalization?

Both our proposal and the Medicare bundled payment demonstrations underway combine acute and post-acute care. It will be difficult for providers who offer care not related to a hospitalization to qualify for the APM payment pathway under MACRA. We need to develop bundles in which all providers can participate and which are not triggered by a hospitalization.

How will bundled payments affect the use of new technology and medications?

Like any APM that sets a fixed payment for a defined set of health care services, bundled payments will have a positive impact by increasing pricing pressure on all the services, medications, and medical devices that providers have to purchase and use to deliver care. But that pricing pressure could also discourage the use of innovations that cost more while improving the quality of care. Placing providers in charge of determining the best care for each patient and using quality standards helps to ensure that providers neither use the most expensive treatments available if they are not necessary nor withholding care which might improve the patient’s outcome. Medicare may have to adjust payments for bundles in response to innovations, and the process for doing so should be transparent so everyone involved can anticipate changes. For shoppable bundles that have a market-based price, innovation poses less of a problem because the added value of an innovation can be reflected in the price that people are willing to pay for it. In addition, paying for care across a time continuum, as bundles do, may help illustrate the cost-effectiveness of new technologies, which may be more expensive initially but which may also lead to improvements in patient outcomes, such as length of stay, readmissions, etc., such that overall costs decrease.

What about other payment reforms like accountable care organizations?

Physicians may wish to use other new payment systems, like accountable care organizations, through which Medicare and providers share in cost savings from improving the efficiency of all the services that a patient needs. Having a choice is important because it is not clear which payment reform will produce the best quality of care for the lowest cost—and Medicare is rightly testing both. Bundled payments and accountable care organizations are also not mutually exclusive—even individual health systems are participating in both arrangements. These scenarios require some delicate accounting, but Medicare is proving that it is possible.

What if ACO payments are lower than bundled payments established under this proposal?

Great! We don’t know whether bundled payments or accountable care organizations will grow faster and whether there may be regional differences in adoption of new models. Having a choice is also important because it is not clear which payment reform will produce the best quality of care for the lowest cost and the two models are not mutually exclusive—even individual health systems are participating in both arrangements. However, we recognize that, as we conceive it, bundled payments would establish rates for just 40% of Medicare fee-for-service spending, while payments to accountable care organizations are comprehensive and cover 100% of Medicare spending for its patient panel. That is why we propose that, within a local health care market, once accountable care organization payments reach a threshold percentage, those payments, and not bundled payments, would be used to establish the Medicare payment baseline for the 60% of Medicare spending not covered under bundles.

Hasn’t CBO already included the adoption of bundle payments in its estimates of current spending?

Yes, to some extent, CBO expects to see initial savings from voluntary adoption of bundled payments. But it would project additional savings from a proposal like this one that uses bundled payments to reset spending projections for non-bundled payments.63